Enter now to win a copy of

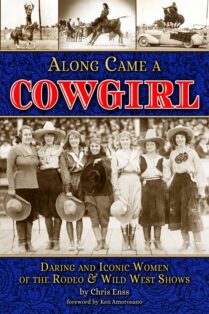

Along Came a Cowgirl:

Daring and Iconic Women of the Rodeos and Wild West Shows

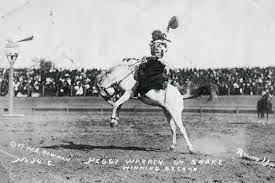

The crowd attending the John Robinson’s Circus in Clarksdale, Mississippi, swelled around the rodeo arena where expert equestrian, roper, and whip cracker Pearl Biron was performing. The twenty-six-year-old Pearl was the master of the Australian bullwhip. She could flick the ashes off the cigarette of a fellow performer or a flag off the head of her horse. Pearl had traveled to Australia early in her career to learn how to use the heavy whip designed for mustering cattle. From atop her roan she could crack the whip through strategically placed targets and flick a row of balls off posts around the stadium. Audiences across the country marveled at her exceptional talent.

Pearl Biron was born in Maine in 1902, and while she was in her late teens became a skilled horseback rider and master of the bull whip. Often billed as the “sweetheart of the rodeo”, Pearl was beautiful as well as clever. She appeared in the arena of a variety of shows including the George V. Adams Rodeo and Col. T. Johnson’s Championship Rodeo.

Pearl was often paired with rodeo circus clown Cherokee Hammond. Pearl would demonstrate her trick riding skills around Cherokee and his mule, Piccolo Pete. Cherokee and Piccolo Pete would play a prospector and his ride heading off to the Gold Rush in their nightly performances. In the show, when the pair found themselves attacked by Indians, Pearl and her horse would ride in to save the day. Critics praised the routine as “thrilling” and “one that spectators thoroughly enjoyed.”

Pearl also won honors for fancy roping and trick horseback riding at Madison Square Garden in New York, and at similar rodeo competitions in Dallas, Texas, and Cheyenne, Wyoming. In 1940, she was billed as the World’s Champion Trick Rider.

The beautiful rodeo performer received standing ovations for her signature trick performed at the close of her time in the arena. Enthusiastic fans selected from the audience would tear sheets of paper in half and give them to members of the rodeo troupe to hold in their mouths. Pearl would ride past the brave members of the troupe and snap the paper out of their teeth with the flick of her whip.

Pearl married Dan H. Biron of Arizona and the couple made a home for themselves and their son in Chandler. Dan was a foreman on a guest ranch, and when Pearl retired from the rodeo, the couple worked together. Pearl would teach guests how to ride and would dazzle them with her bull whip skills at night around the campfire.

Pearl Biron passed away in 1978 at the age of seventy-six.

To learn more about the remarkable women whose names resounded in rodeo arenas across the nation in the early twentieth century read the new book

Along Came a Cowgirl:

Daring and Iconic Women of Rodeos and Wild West Shows by Chris Enss.