Author Chris Enss details Isabella Bird and her journey to Estes Park and her “unlikely friendship” with Rocky Mountain Jim in this American West classic, The Lady and The Mountain Man.

The lure of the fabled Rocky Mountains was an irresistible force for Isabella Bird.

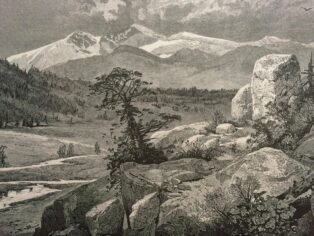

Like many British citizens in the late 19th century, Bird had read stories and heard tales about the majestic American range across the ocean. The air of Colorado’s high altitude offered healing properties for travelers, and its stunning peaks were magnificent sights apt for anyone’s bucket list.

For Bird, who set out from Britain on a steam ship in 1872, the prospect of a visit to the Rocky Mountains was hardly promising or simple. Bird, who had suffered serious health issues since childhood, embarked on the transcontinental journey with a wire cage around her neck, a Victorian medical solution to her weak spine and injured neck.

What’s more, Bird undertook the journey alone, a decision that defied the societal norms and expectations of the time.

“This is in the 1870s, and Bird is a single, Victorian woman in poor health traveling to America,” said author Chris Enss, whose latest book, “The Lady and the Mountain Man,” details Bird’s journey to Colorado in 1873.

Enss’s latest book detailing the history of the American West focuses on Bird’s journey to Estes Park and her “unlikely friendship” with “Rocky Mountain Jim” Nugent, a one-eyed outlaw who guides her to the top of Longs Peak. The book explores Bird’s legacy as an explorer, the colorful characters who resided in Estes Park in the late 19th century and the sometimes-fatal regional struggles for land, power, and influence.

At its heart, however, the book follows a theme that runs throughout Enss’s impressive oeuvre of dozens of books about the American West. The author has long focused on exploring the lives of the women who braved a new frontier in a time of unabashed sexism and structural misogyny. Isabella Bird, who’d gain a reputation as an unparalleled explorer, author, photographer, author, and anthropologist, is a fitting focus for Enss, who’s long worked to spotlight the stories of the women of the West who’ve been overlooked by history.

Throughout her life, Bird’s travels spanned the globe, from Japan to Australia to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) to India, Turkey, and Singapore. Her writings set the standard for international travel and cultural understanding in the 19th century; she was the first woman to be inducted into the Royal National Geographic Society.

For all of her impressive odysseys, Bird’s travels to Colorado served as a watershed in several ways, Enss said.

“The consistency throughout the book is the story of this strong woman who decided that she was going to do something regardless of what the rest of the world said she could or couldn’t do,” Enss said. “Not only were there stereotypes about what women could do in the American west, but she was also an aristocratic woman from Britain,” she added, noting that Bird defied expectations from multiple cultures.

Enss, who drew material from letters, newspaper articles and other primary sources, added that while Bird serves as the central figure of the book, “The Lady and the Mountain Man” offers readers multiple narrative tracks and simultaneous threads. As the book’s title indicates, the story explores the unique relationship between Bird and Jim Nugent, a grizzled outlaw out of a Western storybook who also boasted a penchant for poetry, literature, and history. As Bird herself noted, he was a “man any woman might love but no sane woman would marry.”

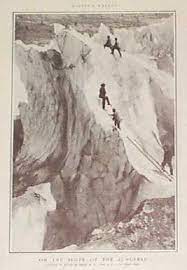

Bird, who called Nugent her “dear desperado,” forged a relationship with Nugent as they ascended Longs Peak together, a harrowing journey that would’ve been challenging for even the most experienced mountaineer.

“It was incredibly difficult. They did not have any of the fineries that people have now. She speaks a lot about the difficulty in crossing the lava bed, with all the jagged rocks. Her footing wasn’t so good,” Enss said, citing reports initially spelled out in Bird’s letters to her sister at home, accounts that ultimately figured into her book “A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains.” “It was cold. There were lots of wild animals that seemed to be stalking them.”

As the pair braved those risks in the day, and bonded around the campfire at night, their relationship took on a different dimension, Enss notes. The journey offered an opportunity for both to reveal their character – they swapped verses of poetry, discussions about the Bible and meditations about Shakespeare. According to one of her letters, Nugent “told stories of his early youth, and of a great sorrow which had led him to embark on a lawless and desperate life.”

That combination of peril and intimacy left an indelible mark, Enss said.

“It results with the pair falling in love,” she said. “He drank in excess, he was crude. But at one point he had studied to be a priest. He was a poet, and he could quote Shakespeare. Going up to Longs Peak in the evenings, he regaled her with his verses.”

This unlikely bond builds against a backdrop of frontier conflicts and violence. Lord Dunraven, an aristocrat who owned land in the Estes Park area, was intent on claiming large swaths of the area for hunting preserves and other purposes, wanted to get rid of Nugent and drive him from his land. That conflict would ultimately claim Nugent’s life, after Bird left Colorado for further international journeys.

“The book really is in three parts. You have the part with Isabella and Jim; there’s the Lord Dunraven portion of the story and his combative relationship; but you also have Isabella Bird, who as she’s getting healthier, tours the Rocky Mountains by herself,” Enss said, adding that journey ultimately served as a transformative experience – after her time in Colorado, Bird no longer wore the wire cage to support her neck and back. “That was unheard of in 1873 for a woman to do.”

A through-line that undergirds all elements of the book is the setting. Enss has long explored different sites and locales in the American West, but this tome offered the author the opportunity to spotlight Colorado and the Estes Park region as its own character.

“Colorado is a character in and of itself. That’s really important in this book,” she said, adding that the setting and the main character combined to make this piece unforgettable in her 50-plus book bibliography. “Of all the people who I’ve written about (more than 50 books), I’ll miss her the most. She was just an inspired human being.”

Enter now to win a copy of The Lady and the Mountain Man