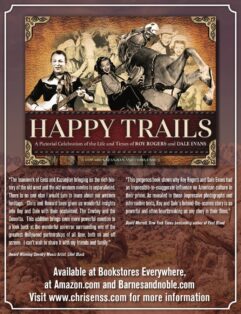

Enter now to win a copy of

Happy Trails: A Pictorial Celebration of the Life and Times of Roy Rogers and Dale Evans

Dale Evans was one of Republic Pictures most popular western stars. The unlikely celluloid cowgirl, western star starred in tandem with singing cowboy Roy Rogers in most of her thirty-eight films and two television series. The undisputed Queen of the West was born Frances Octavia Smith on October 31, 1912, Uvalde, Texas. In her words, her upbringing was “idyllic.” As the only daughter of Walter and Betty Sue Smith, she was showered with attention and her musical talents were encouraged with piano and dance lessons.

While still in high school, she married Thomas Fox and had a son, Thomas Jr. The marriage, however, was short-lived. After securing a divorce, she attended a business school in Memphis and worked as a secretary before making her singing debut at a local radio station. In 1931 she changed her name to Dale Evans.

By the mid-1930s, Dale was highly sought-after big-band singer performing with orchestras throughout the Midwest. Her stage persona and singing voice earned her a screen test for the 1942 movie Holiday Inn. She didn’t get the part, but she ended up singing with the nationally broadcast radio program the Chase and Sanborn Hour and soon after signed a contract with Republic Studios. She hoped her work in motion pictures would lead to a run on Broadway doing musicals.

In August 1943, two weeks after signing a one-year contract with Republic Studios, Dale began rehearsals for the film Swing Your Partner. Although her role in the picture was small, studio executives considered it a promising start. Over the next year Dale filmed nine other movies for Republic, and in between she continued to record music.

When she wasn’t working, Dale spent time with her son, Tom, and her second husband, orchestra director Robert Butts. Her marriage was struggling under the weight of their demanding work schedules, but neither spouse was willing to compromise.

“I was torn between my desire to be a good housekeeper, wife, and mother and my consuming ambition as an entertainer,” Dale told the Los Angeles Daily News in 1970. “It was like trying to ride two horses at once, and I couldn’t seem to control either one of them.”

Dale’s marriage might have been suffering, but her career was taking off. Republic Studio’s president Herbert Yates summoned Dale to a meeting to discuss the next musical the studio would be doing. She took this as a hopeful sign. It was common knowledge around the studio lot that Yates had recently seen a New York stage production of the music Oklahoma and had fallen in love with the story. Dale imagined that the studio president wanted to talk with her about starring in a film version of the play. It was the opportunity she had always envisioned for herself. For a brief moment she was one step closer to Broadway.

Dale Evans dreamed of starring as the lead in the film version of Oklahoma, but Republic president Herbert Yates had other plans for the actress. He wanted her to play opposite the studio’s star cowboy in the movie The Cowboy and the Senorita.

Dale’s only experience in westerns had been a small role as a saloon singer in a John Wayne picture, and she was not a skilled rider. She committed herself to doing her very best, however, in the role of the “Senorita,” Ysobel Martinez.

The picture was released in 1944 and was a huge success. Theatre managers and audiences alike encouraged studio executives at Republic to quickly re-team Dale and Roy in another western.

In between her film jobs, Dale toured military bases in the United States with the USO. She sang to troops on bivouac, from Louisiana to Texas. She was proud to think she was bringing a little sunshine into the hearts of the soldiers.

Dale also brought sunshine into the hearts of moviegoers, and ticket sales were evidence of that. Republic had happened onto the perfect western team. Dale was a sassy, sophisticated leading lady and the perfect foil for Roy, the patient, singing cowboy.

The Cowboy and the Senorita was a big hit for Republic. The April 1944 edition of Movie Line Magazine heaped praise on the film and its’ stars. “Intrigue and song fill the Old West when America’s favorite singing cowboy rides to the rescue of two unfortunate ladies about to be swindled out of their inheritance,” the magazine article read.

“In Republic Pictures’ latest film The Cowboy and the Senorita, Roy Rogers and his sidekick Guinn “Big Boy” Williams, amble into a busy frontier berg looking for work and are mistakenly identified as felons. Roy and Williams’ character “Teddy Bear” are accused of kidnapping 17-year-old Chip Martinez, played by Republic Pictures singing sensation, Mary Lee. In truth, Chip has run away from home and her cousin, Ysobel, played by talented newcomer Dale Evans, to hunt for a buried treasure.

“Roy convinces Ysobel that he had nothing to do with her cousin’s disappearance and offers to help find the teenager. Rearing on his famous palomino Trigger, Roy and Teddy Bear comb the countryside until they find Chip. The pair is then hired on to work on the Martinez ranch and to watch over the impetuous Chip. Desperate to get away again, Chip tells the boys she wants to find the treasure buried in a supposedly worthless gold mine she inherited from her father. They agree to lend the young girl a hand in spite of her cousin’s objections.

“Meanwhile, Ysobel has promised to sell the mine to her boyfriend Craig Allen, played by John Hubbard. Allen is a charming gambler and town boss who has convinced the unsuspecting Ysobel the mine has no value. Allen of course knows differently.

“Using a clue left by Chips father, Roy investigates the mine and discovers a hidden shaft that contains the gold. The boys must outride Allen’s men who are determined to stop Rogers and his sidekick at any cost. Our heroes are in a race against time and a posse. They must get ore samples back to town before the ownership of the mine is transferred.

“The action in The Cowboy and the Senorita is heightened with several song and dance numbers performed by Roy Rogers, the Sons of the Pioneers, and Dale Evans. Songs include the title tune, Round Her Neck She Wore A Yellow Ribbon, Bunk House Bugle Boy, and Enchilada Man. The chemistry between Roy Rogers and Dale Evans is enchanting and “Big Boy” Williams adds great comic relief as Roy’s riding partner.

“The King of the Cowboys and Trigger will ride the range again this fall in their next picture The Yellow Rose of Texas. Roy will be paired with Dale Evans for a second time in this feature. He’ll be playing an insurance investigator working undercover on Dale’s showboat. No doubt Rogers’ 900,000 fans will flock to the theatre to watch him ride to the rescue.”

Herbert Yates was quick to capitalize on the success of The Cowboy and the Senorita and the chemistry between Roy Rogers and Dale Evans. The motion picture executive decided to stay the pair in three more westerns, Yellow Rose of Texas, Lights of Old Santa Fe, and San Fernando Valley.

Audiences flocked to theatres to see Dale Evans opposite Roy and his horse Trigger. She received sacks of mail from fans of all ages complimenting her on her acting and singing and expressing their desire to see her continue starring with Roy in more westerns.

With the exception of the motions picture The Big Show Off, Dale’s admirers would get their wish.

Republic Pictures The Big Show Off was released in January 1945 and in addition to Dale Evans it starred Arthur Lake and Lionel Stander. Dale portrayed a night club singer being romantically pursued by the piano player at the club. In order to get Dale’s attention, the musician disguises himself as a professional wrestler. He is aware of Dale’s character’s fascination with professional wrestling and he hopes if he manages to make a name for himself in the ring, she will fall in love with him.

Movie critics and fans alike appreciated Dale’s work. The actress had “many sides to her talent,” the February 15, 1945 edition of the Hollywood Reporter noted. “Not only can she dance and sing as well as act, but she also writes her own songs. There’s Only One You which she sings in The Big Show Off is one of her own compositions.”

Dale’s departure from westerns was short lived. Utah, Bells of Rosarita, Man from Oklahoma, Along the Navajo Trail, Sunset in El Dorado, and Don’t Fence Me In were all released in 1945. Each starred Roy and Dale along with Trigger and there were many more films to come.

Throughout the 1940s the careers of Roy Rogers and Dale Evans rode the crest of an incredible wave. Their popularity spanned across the ocean into Europe, and fans who wanted their heroes with them at all times could purchase toothbrushes, hats, dishes, and bed sheets with the pair’s names and likenesses on every item. By the late 1940s Roy Rogers and Dale Evans were second only to Walt Disney in commercial endorsements. They played to record-breaking crowds at rodeos and state fairs.

Roy and Dale were together most of their waking hours. They were good friends who confided in each other and discussed the difficulties of being single parents. Roy’s wife had died after giving birth to their son and Dale had divorced her third husband. They depended on one another and respected each other’s talents. Roy was impressed with Dale’s on-screen take-charge personality. Dale had a quick, smart-aleck delivery, and she wasn’t afraid to get into a fight or two.

In the fall of 1947 Roy proposed to Dale as he sat on Trigger. The pair was performing at a rodeo in Chicago, and moments before their big entrance Roy suggested they get married. The date set for the wedding was New Year’s Eve. Gossip columnist predicted that Trigger would be the best man and that Dale would wear a red-sequined, cowgirl gown. The predictions proved to be false.

Roy and Dale’s wedding was a simple affair held at a ranch in Oklahoma, which happened to be the location for the filming of their seventeenth movie, Home in Oklahoma.

Roy Rogers continued to reign as King of the Cowboys after he and Dale married, but his wife was temporarily dethroned from her honorary role as the Queen of the West. Republic Studios believed the public would not be interested in seeing a married couple teamed together, and a series of new leading ladies took Dale’s place on screen. Ticket buyers did not respond well to the new women. It wasn’t long before Republic executives decided to reinstate Dale and begin production on another film that would re-team the popular pair.

In between filming their westerns, Roy and Dale kept busy recording some of Dale’s compositions for RCA Victor records. Their song Aha, San Antone sold more than 200,000 copies. Roy and Dale were also doing a radio show, performing at rodeos, and keeping up with personal-appearance tours that took them all over the United States.

When Roy Rogers parted company with Republic Pictures in 1951, Dale went with him. The cowboy duo decided they would try their hand at television. Both Roy and Dale were among the top-ten money-making western stars in the industry. Network executives at the National Broadcasting Corporation believed their audience would follow them to the new medium. The Roy Rogers Show ran from 1951 to 1957. The song Dale Evans wrote for the T. V. show entitled Happy Trails, has endured through the decades.

Dale Evans died from congestive heart failure on February 7, 2001. The movies she made with Republic Pictures continue to air on various western channels today and prove she still reigns as Queen of the Cowgirls.

To read more about Dale Evans and her life with Roy Rogers read Happy Trails