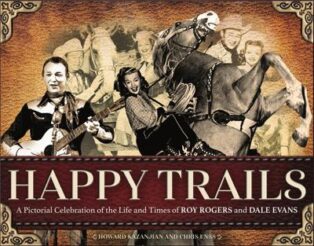

Enter now to win a copy of

Happy Trails: A Pictorial Celebration of the Life and Times of Roy Rogers and Dale Evans

Hundreds of excited children, with hard-earned nickels and dimes clutched tightly in their fists, exchanged their money for a ticket at Saturday matinees across the country in the 1940s. The chance to see singing cowboy Roy Rogers, his horse, Trigger, and leading lady Dale Evans come up against the West’s most notorious criminals brought young audiences to theatres in droves. And, in the process, it elevated western musicals to one of the most popular film genres in history.

Roy Rogers and Dale Evans were the reigning royalty of B-rated westerns for more than a decade. They helped persuade moviegoers that good always triumphs over evil in a fair fight and that life on the open range was one long, wholesome sing-along. Together, the King of the Cowboys and the Queen of the West appeared in more than 200 films and television programs.

Roy and Dale made their first pictures together in 1994. The film, The Cowboy and the Senorita, brought an estimated 900,000 fans to movie houses in America and began a partnership for the couple that lasted fifty-two years. The chemistry between Roy and Dale was enchanting, and together they were an entertainment powerhouse. In addition to their films, they had popular radio programs, comic book series, albums, and a long list of merchandise (including clothes, boots, and toys), all bearing their names.

Roy and Dale were successful individuals, as well, Dale, a talented singer-songwriter, performed with big band orchestras, shared the stage with Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, and penned many popular tunes, including the song that would be Roy and Dale’s theme, “Happy Trails.” Roy was a co-founder and member of the group the Sons of the Pioneers. The band made a name for itself singing original country music songs, including “Cool Water” and “Tumblin’ Tumbleweeds.”

Roy Rogers and Dale Evans were married in 1947. As a couple they were consistently ranked in the top ten among the western stars at the box office. They costarred in twenty-nine movies and recorded more than 200 albums together. In 1951, they parlayed their fame to the small screen, appearing in a half-hour television show aptly called The Roy Rogers Show.

When they weren’t working, the western icons spent a great deal of time visiting children in hospitals and orphanages. They were dedicated Christians who sought to serve the hurt and needy. They would later be recognized by national civic organizations for their humanitarian efforts.

Roy and Dale’s off-screen life was filled with a great deal of love and happiness. They had nine children, whom they adored and showered with affection. Their family was no stranger to tragedy though. One child, Robin, died of complications associated with Down syndrome. An adopted daughter, Debbie, died in a church bus accident when she was twelve; their adopted son, Sandy, suffered as accidental death while serving in the military in Germany. Robin’s death inspired Dale to write Angel Unaware, the first of her more than twenty books.

After the couple was semi-retired from the entertainment industry, they greeted fans at the museum in Victorville, California, and enjoyed life with their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Thousands of western enthusiasts and fans alike now make the pilgrimage to Branson, Missouri, where the Roy Rogers-Dale Evans Museum is currently located. They come to get a glimpse of their heroes’ six-shooters, boots, costumes, and other personal artifacts on display.

The Rogers family’s collection of priceless items elicits fond memories of an inspirational pair who used their immense talent to encourage moral and spiritual strength. The artifacts draw visitors back in time to when knights of the American plains yodeled, wore white hats and fancy boots, and thrived on defeating the outlaws and rescuing the defenseless.