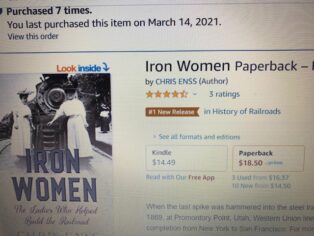

Enter now to win a copy of

Principles of Posse Management:

Lessons from the Old West for Today’s Leaders

Five riders moved swiftly across the open country through Granite Pass in southwest New Mexico. An electrical storm lit up the sky around them, and a deluge of hail broke free from the clouds, pelting the men in their saddles and their horses. Sounding like a troop of demons advancing, the wind howled and screamed as it pushed over the massive walls of rock the riders passed.

Former peace officer Jefferson Davis Milton rode in front of the others. He was a tall man with sloping shoulders, his granite like visage partly hidden by a dark mustache that curled around to meet his thick sideburns. George W. Scarborough, a blue-eyed, gruff looking, one time law man from El Paso, Texas, took a position on Jeff’s left. Eugene Thacker, a youthful son of a railroad detective, rode on Jeff’s right side. Directly behind the three were Bill Martin and Thomas Bennett, Diamond A ranch cowboys turned bounty hunters. The men pulled their slickers around their necks and urged their mounts on through the tempest. Claps of thunder ushered in another downpour of hail.

The determined riders, members of a posse pursuing a gang of train robbing outlaws, were soaked to the bone once they reached Fort Apache, a military post near Coolidge Lake. No one said a word as they made camp outside the garrison’s gates. Discussing the obstacles on the way to achieving that goal wasn’t necessary. Their focus was on capturing Bronco Bill Walters and his boys.

William E. Walters, also known as Bronco Bill Walters, was from Fort Sill, Oklahoma. What he did before being hired at the Diamond A ranch in 1899 is anyone’s guess. It’s what he did after getting a job as a cowhand that warranted attention. The Diamond A was a five hundred square mile spread nestled in the boot heel of New Mexico. The magnificent acres of grass there made it the perfect spot for raising cattle. The ranch was always in need of workers. Cowpunchers that dropped by looking for employment were generally hired on the spot. It was considered a rude violation of the proprieties of a cow camp to inquire into a man’s connections or character. Just wanting to work was enough. Bronco Bill Walters wanted to work, and that’s all that mattered and all the foreman at the Diamond A would have cared about if Bronco Bill hadn’t had desired more than the job had to offer.

During long, dull evenings around the campfire, Bronco Bill contemplated a life that was exciting and profitable. He thought about robbing a stage or a train. He imagined how he would tackle such a daring feat and rehearsed a getaway. After a while, it wasn’t enough only to imagine such actions. Bronco Bill left the Diamond A ranch in the fall of 1890 in search of excitement and money.

To learn more about Bronco Bill and the posse after him read

Principles of Posse Management.