Enter now to win a Blizzard of Books.

You could win twelve autographed copies of books from my catalog of books if you sign up to receive my newsletter, share this post,

and follow me on Facebook and Twitter.

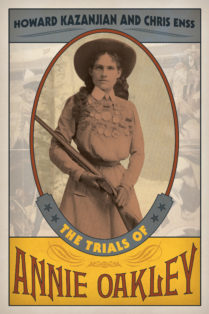

You could win a copy of The Trials of Annie Oakley.

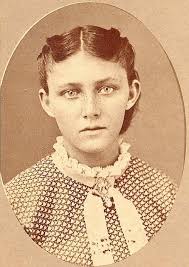

Long before the screen placed the face of Mary Pickford before the eyes of millions of Americans, this girl, born August 13, 1800 and who was christened Phoebe Anne Oakley Moses and was destined to make the shortened form her name, “Annie Oakley,” known throughout the world, had won the right to the title of the first “America’s Sweetheart.”

The life story of Annie Oakley is a combination Cinderella fairy story and frontier melodrama.

The Cinderella part of it begins with the pioneer home near a small cross-roads settlement to Darke County, Ohio, where in a little log cabin lived Jake Moses and his wife, whom, as a twelve-year-old child he had rescued from a brutal stepfather in Pennsylvania. He had given her a home with her sister and, after marrying her, when she was fifteen, set out with her to make a new home in the Ohio country. In this new home Moses and his wife fought a constant battle with privation and poverty. Then Moses returning from the saw mill, was frozen to death in a blizzard and upon the mother fell the whole task of carrying for her seven children.

At the age of six Annie began helping fill the family larder by trapping quail and a few years later she had made the first start on the rifle career that made her famous. One of the few possessions that Jake Moses had brought with him from Pennsylvania was a 40 inch cap and ball Kentucky rifle which hung over the fireplace, but which had never been used because Moses was a Quaker with the Quaker prejudice against firearms. The tomboy Annie, however, did not share that prejudice. She saw in the weapon an instrument for getting more food for her brothers and sisters, and finally gained her mother’s reluctant consent.

But the beginning of her career as a markswoman was soon interrupted. She went to the country infirmary to get the chance to attend school and while there a stranger appeared and offered to take one of the girls at the infirmary to work for her “board and keep.” Annie was the girl selected and in the home of this man began her Cinderella existence. The man was a brute and his wife a virago. Annie was held as a virtual slave subjected to all sorts of cruel treatment. Once when she fell asleep over a basket of mending the woman threw her out into a snowstorm half-naked. After two years of this existence she finally escaped and returned home.

There she continued her former role of provider for the family with the rifle and thus laid the foundation for the marvelous skill which was to make her world famous. News of her skill spread throughout Darke County and even to Cincinnati where hotel keepers had been buying the game which she killed. When Annie was fifteen there came to Cincinnati the “far-famed team of Butler and Company, performing deeds of daring and dexterity with firearms, seldom exhibited before the eyes of an audience. As a publicity stunt, Frank E. Butler was accustomed to issue a challenge to all comers to a shooting match. The challenge was taken up by one of Annie’s hotel keeping patrons who prevailed upon her to shoot against the professional.

The girl not only won the match, but also won the heart of Frank Butler and a year or so later they were married. Frank often wrote Annie poems that shared his plans for their future together.

Some find day I’ll settle down

And stop this roving life.

With a cottage in the country

I will claim my little wife.

Then we will be happy and contented,

No quarrels shall arise

And I’ll never leave my little girl

With the rain drops in her eyes.

Annie eventually began taking part in her husband’s act and for some time they were billed as “Butler and Oakley.” Then Butler, who was a skillful showman, began giving his wife more and more of the limelight and pushing himself more and more into the background. Within a short time, Annie was a noted figure in the Wild West theater.

“What fools we mortals be! Annie once wrote of her beloved husband. “My admiration for Frank Butler’s poodle led me into signing some sort of alliance papers with him that tied a knot so hard it lasted some fifty years.”

Enter now to win a Blizzard of Books!