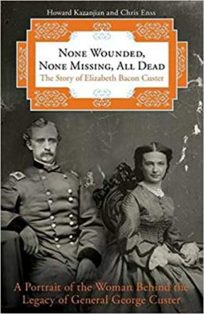

Enter now to win a copy of

None Wounded, None Missing, All Dead: The Story of Elizabeth Bacon Custer

It was almost two in the morning, and Elizabeth Custer, the young wife of the famed “boy general” George, couldn’t sleep. The heat kept her awake—a sweltering intense heat that had overtaken Fort Lincoln in the Dakota Territory earlier that day. Even if the conditions had been more congenial, however, sleep would have eluded Elizabeth. The rumor that had swept through the army post around lunchtime disturbed her greatly, and, until this rumor was confirmed, she doubted that she’d be able to get a moment’s rest.

Elizabeth, or Libbie as her husband and friends called her, carried her petite, slender frame over to the window and gazed out at the night sky. It had been more than two weeks since she had said good-bye to her husband. She left him and his battalion a few miles outside the fort. George had orders from his superior officers in Washington, DC, to “round up the hostile Indians in the territory and bring about stability in the hills of Montana.” Elizabeth knew he would do everything in his power to fulfill his duty.

George and Elizabeth said their good-byes, and she headed back to the fort. As she rode away, she turned around for one last glance at General Custer’s column departing in the opposite direction. It was a splendid picture. The flags and pennons were flying, the men were waving, and even the horses seemed to be arching themselves to show how fine and fit they were. George rode to the top of the promontory and turned around, stood up in his stirrups, and waved his hat. They all started forward again and, in a few seconds, disappeared—horses, flags, men, and ammunition all on their way to the Little Bighorn River. That was the last time Elizabeth saw her husband alive.

Over and over again, she played out the events of the hot day that had made her restless. She and several other wives had been sitting on the porch of her quarters singing, reluctant for some inexplicable reason to go inside. All at once they noticed a group of soldiers congregating and talking excitedly. One of the Native scouts, a man named Horn Toad, ran to them and announced, “Custer killed. Whole command killed.” The women stared at Horn Toad in stunned silence. Finally, one of the wives asked the man how he knew that Custer was killed. He replied, “Speckled Cock, Indian scout, just come. Rode pony many miles. Pony tired. Indian tired. Say Custer shot himself at end. Say all dead.”

Elizabeth remembered George’s warning about trusting in rumors. She believed that there might have been a skirmish but felt it unlikely that an entire command could be wiped out. At that moment, she refused to believe George would ever dare die. She would wait for confirmation before she did anything else. Now, in her bedroom, listening to the chirping of the crickets and the howls of the coyotes, she sat up, wide awake, waiting.

The loud sound of boots tromping across the path toward her front door gave her a start. She hurried to the door and threw it open. Captain William S. McCaskey entered her home, holding his hat in his hands. He didn’t want to be there. Elizabeth looked at him with eyes pleading. “None wounded, none missing, all dead,” he sadly reported. Elizabeth stood frozen for a moment, unable to move, the color drained from her face.

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Custer,” the captain sighed. “Do you need to sit down?”

Elizabeth blinked away the tears. “No,” she replied. “What about the other wives?”

“We’ll let them know of their husbands’ fates,” he assured her.

Despite the intense heat, Elizabeth was now shivering. She picked up a nearby wrap and draped it around her shoulders. Her hands were shaking. “I’m coming with you,” she said, choking back the tears. “As the wife of the post commander it’s my duty to go along with you when you tell the other . . . widows.” The captain didn’t argue with the bereaved woman. He knew there would be no point. Elizabeth Custer was as stubborn as her general husband—if not more so.

To learn more about the champion of the Seventh Cavalry read

None Wounded, None Missing, All Dead: The Story of Elizabeth Bacon Custer