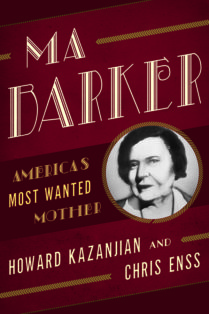

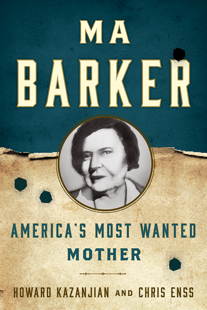

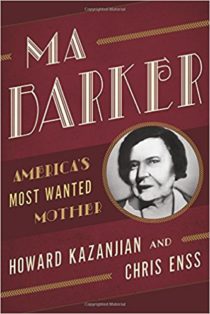

Enter now to win a copy of

Ma Barker: America’s Most Wanted Mother

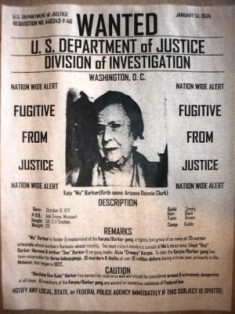

In a time when notorious Depression-era criminals were terrorizing the country, the Barker-Karpis Gang stole more money than mobsters John Dillinger, Vern Miller, and Bonnie and Clyde combined. Five of the most wanted thieves, murderers, and kidnappers by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the 1930s were from the same family. Authorities believed the woman behind the band of violent hoodlums that ravaged the Midwest was their mother, Kate “Ma” Barker.

Fred Barker sat in a dark corner at Tallman’s Grill in Kansas City, Missouri, enjoying the music of a jazz troupe. He was situated behind a lavishly decorated table loaded with steaks, oysters, and frogs’ legs. He was waiting for his date, Paula Harmon, also known as Polly Walker. She attracted more than casual attention when she finally arrived. The amply built, full-fleshed woman with reddish-blonde hair wore a stylish gown suited for an evening out. A silver fox-fur cape was draped over her shoulders, and on her left hand was a ring studded with eight diamonds. She was twenty-nine years old and had a reputation for treating men with flirtatious condescension, as if they were children.

In spite of objections from friends and family, Fred enjoyed Paula’s company. She possessed an average face, hazel eyes, and a scarred nose, which gave the impression that she had been struck by a heavy instrument. She greeted Fred with a kiss, and he helped her into her chair. The two always had a great deal to talk about; they had a lot in common. Fred liked to shower her with gifts as well, and Paula liked to accept them.

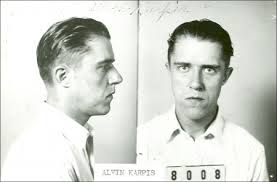

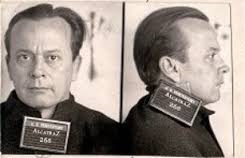

“Girls liked Freddie and he didn’t mind spending money on them,” Alvin Karpis wrote in his memoirs. “But he wasn’t always lucky in the type of broad who hooked him. Paula Harmon turned out to be a rotten choice, though you couldn’t tell that to Freddie when he got stuck on her. Paula was a drunk too.”

Fred wasn’t the first gangster to overlook Paula’s drinking. She was the widow of bank robber Charles Harmon. Charles died from a gunshot wound in the neck he received fleeing the scene of a bank robbery in Menomonie, Wisconsin. Paula, a native of Georgia, earned her living operating a house of ill –repute in Chicago. Patrons referred to her as “Fat Witted” because she had a sharp tongue when provoked.

Paula and Fred met at Herbert Farmer’s homestead near Joplin, Missouri, shortly after her husband died. The Farmers were good friends who helped her through the loss and protected her from questions the police might have wanted to ask her. Fred thought Paula was charming, and she liked the attention he gave her.

After helping rob the bank in Fairbury, Nebraska, Fred made it clear to his associates that he wanted to spend time with a woman, away from the business. Verne Miller’s paramour suggested he reacquaint himself with Paula. Fred and Paula met again in mid-April 1933 in St. Paul and then traveled to Kansas City for a brief vacation. The pair used the alias of Mr. and Mrs. J. Stanley Smith. Mrs. Smith was a housewife, and Mr. Smith posed as a salesman for the Federated Metal Company of St. Louis.

To learn more about Ma Barker and the Barker-Karpis Gang read

Ma Barker: America’s Most Wanted Mother.