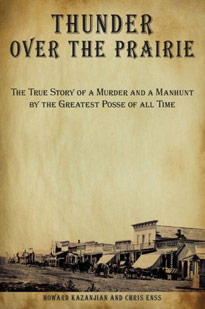

Enter to win a copy of

Thunder Over the Prairie:

The Story of a Murder and a Manhunt by the

Greatest Posse of All Time.

Dora Hand was in a deep sleep. Her bare legs were draped across the thick blankets covering her delicate form and a mass of long, auburn hair stretched over the pillow under her head and dangled off the top of a flimsy mattress. Her breathing was slow and effortless. A framed, graphite- charcoal portrait of an elderly couple hung above her bed on faded, satin-ribbon wallpaper and kept company with her slumber.

The air outside the window next to the picture was still and cold. The distant sound of voices, back-slapping laughter, profanity, and a piano’s tinny, repetitious melody wafted down Dodge City, Kansas’s main thoroughfare and snuck into the small room where Dora was laying.

Dodge was an all-night town. Walkers and loungers kept the streets and saloons busy. Residents learned to sleep through the giggling, growling, and gunplay of the cowboy consumers and their paramours for hire. Dora was accustomed to the nightly frivolity and clatter. Her dreams were seldom disturbed by the commotion.

All at once the hard thud of a pair of bullets charging through the wall of the tiny room cut through the routine noises of the cattle town with an uneven, gusty violence. The first bullet was halted by the dense plaster partition leading into the bed chambers. The second struck Dora on the right side under her arm. There was no time for her to object to the injury, no moment for her to cry out or recoil in pain. The slug killed her instantly.

In the near distance a horse squealed and its galloping hooves echoed off the dusty street and faded away.

A pool of blood pored out of Dora’s fatal wound, transforming the white sheets she rested on to crimson. A clock sitting on a nightstand next to the lifeless body ticked on steadily and mercilessly. It was 4:30 in the morning on October 4, 1878, and for the moment, nothing but the persistent moonlight filtering into the scene through a closed window recognized the 34 year-old woman’s passing.

Twenty-four hours prior to Dora being gunned down in her sleep she had been on stage at the Alhambra Saloon and Gambling House. She was a stunning woman whose wholesome voice and exquisite features had charmed audiences from Abilene to Austin. She regaled love starved wranglers and rough riders at stage and railroad stops with her heartfelt rendition of the popular ballads Blessed Be the Ties That Bind and Because I Love You So.

Adoring fans referred to her as the “nightingale of the frontier” and admirers competed for her attention on a continual basis. More times than not pistols were used to settle arguments about who would be escorting Dora back to her place at the end of the evening. Local newspapers claimed her talent and beauty “caused more gunfights than any other woman in all the West.”

The gifted entertainer was born Isadore Addie May on August 23, 1844 in Lowell, Massachusetts. At an early age she showed signs of being a more than capable vocalist, prompting her parents to enroll her at the Boston Conservatory of Music. Impressed with her ability, instructors at the school helped the young ingénue complete her education at an academy in Germany. From there she made her stage debut as a member of a company of operatic singers touring Europe.

After a brief time abroad, Dora returned to America. By the age of twenty-four she had developed a fondness for the vagabond lifestyle of an entertainer and was not satisfied being at any one location for very long. The need for musical acts beyond the Mississippi River urged her west and appreciative show goers enticed her to remain there.

To learn more about the most intrepid posse of the Old West read

Thunder Over the Prairie.