Last chance to enter to win a copy of More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

Lynn died in a gun battle with Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation agent Crockett Long in Mandill, Oklahoma. On July 17, 1932, an inebriated Lynn confronted Agent Crockett with his pistol drawn. The agent quickly drew his weapon, and the two fired at one another at the same time. Both Agent Crockett and Wi“He died for the state he helped create. He set an example of modesty and courage that few could match, yet he made us all better men for trying.”

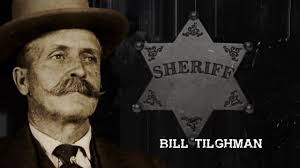

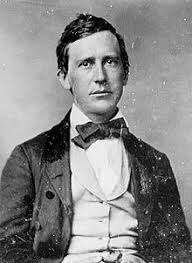

— Governor Martin E. Trapp speaking at the funeral of Bill Tilghman

Legendary lawman and sportswriter Bat Masterson once referred to his well-known colleague Bill Tilghman as “the finest among us all.” Marshall Tilghman and Sheriff Bat Masterson were two members of the “most intrepid posse” of the Old West, a group of policemen who, in 1878, tracked down the killer of a popular songstress named Dora Hand.

William Matthew Tilghman, Jr.’s drive to legitimately right a wrong began at an early age. He was born on the Fourth of July 1854 in Fort Dodge, Iowa. His father was a soldier turned farmer, and his mother was a homemaker. Bill spent his early childhood in the heart of the Sioux Indian territory in Minnesota. Grazed by an arrow when he was a baby, he was raised to respect Native Americans and protect his family from tribes that felt they had been unfairly treated by the government. Bill was one of six children. His mother insisted he had been “born to a life of danger.”

In 1859 his family moved to a homestead near Atchison, Kansas. While Bill’s father and oldest brother were fighting in the Civil War, he worked the farm and hunted game. One of the most significant events in his early life occurred when he was twelve years old while returning home from a blackberry hunt. His hero, Bill Hickok, rode up beside him and asked if he had seen a man ride through with a team of mules and a wagon.

The wagon and mules had been stolen in Abilene, and the marshal had pursued the culprit across four hundred miles. Bill told Hickok that the thief had passed him on the road that led to Atchison. The marshal caught the criminal before he left the area and escorted him back to the scene of the crime. Bill was so taken by Hickok’s passion for upholding the law that he decided to follow in his footsteps and become a scout and lawman.

From 1871 to 1888, Bill hunted buffalo, rounded up livestock, scouted for the military, and operated a tavern in Dodge City, Kansas. In 1889, Bill settled in Oklahoma and was at once appointed deputy United States marshal, thus taking to a calling that made him famous as a hustler of outlaws of the most desperate kind. During his term in office, he amassed a fortune in rewards paid by the government for the capture of such noted desperados, train robbers, bank robbers, and murderers as Bill Doolin, Tulsa Jack, Bitter Creek, and Bill Dalton.

In his many years of continuous service as United States marshal, Bill was the associate of such noted scouts as Luke Short, Pat Garrett, Wild Bill Hickok, Neal Brown, and Charley Bassett. Bat Masterson was also one of the famous marshals of Dodge City in the early days and knew Bill Tilghman well. The two were lifelong friends. Masterson once said of Tilghman, “After a career of sixteen years on the firing lines of America’s last frontier and after being shot at five hundred times by the most desperate outlaws in the land, whose unerring aim with a six-shooter or Winchester seldom failed to bring down their victims, this man, Bill Tilghman, came through it all unscathed, and is perhaps the only frontiersman who has been constantly on the job for more than a generation and lives to tell the tale.”

Bill Tilghman was twice elected sheriff of Lincoln County, Oklahoma, after which he was elected to the state senate, resigning that office to accept the job of chief of police of Oklahoma City. He would resign that position in 1914 to campaign for United States marshal in Oklahoma. Bill received the appointment and rendered valuable service not only during that term but also at various other times he had the post.

In 1924 Bill was persuaded to take on the job of cleaning up a lawless oil boomtown called Cromwell in Oklahoma. He was seventy-one years old when he was shot in an ambush on Saturday, November 1, 1924, by a corrupt Prohibition enforcement officer. Wiley Lynn, the man who shot the aged officer, fled the scene of the crime but gave himself up to authorities in Holdenville, Oklahoma. Lynn admitted to officers at Holdenville that he shot Bill, but would make no further statement. He was placed in the Hughes County jail to await formal action by the authorities.

Cromwell had long been known as a “wide open” town. Dance halls and gambling joints had been running freely, and booze was easy to obtain. Vice conditions were regarded as so bad that federal authorities had been dispatched to the area. Lynn was one of a handful of agents sent to the territory.

Conditions in Cromwell did not get any better with the presence of the federal authorities. When the situation escalated, a step toward more law enforcement was made, and Bill was called in to serve in the role in which he had gained fame. Now he no longer was the Bill of the old days when his daring speed on the trigger made him respected and feared by all law breakers. Conditions improved somewhat, however, and there were indications that a complete cleanup there might be made.

The fatal shooting occurred when Bill attempted to place under arrest members of a motorcar party who were disturbing the peace on the main street of town. One of the men fired a pistol shot into the air, and a few minutes later spectators heard angry words and another shot. Bill fell and was dead before anyone reached him.

After shooting Marshal Tilghman, the slayer fled in the car, occupied by another man and two women, and drove rapidly out of town. Wiley Lynn was arrested and tried for killing Bill but was found not guilty of murder. The jury believed he had acted in self-defense.

Eight years after killing Marshal Tilghman, Wiley ley Lynn died as a result of gunshot wounds.

Graveside services for lawman Bill Tilghman were held at Oak Park Cemetery in Lincoln County, Oklahoma.

To learn more about the deaths of legendary western characters read

More Tales Behind the Tombstones:

More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen