Enter now to win a copy of

Cowboys, Creatures and Classics: The Story of Republic Pictures

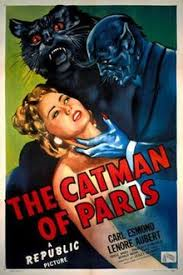

A dark figure weaves through a forest of imposing, leafless trees toward a weathered cabin in a clearing. An eerie mist blankets the ground, and a lone wolf howls in the distance. Inside the cabin, two men dressed in business suits and fedoras discuss plans to steal a counter atomic bomb device called the Cyclotrode. Their conversation is interrupted when the door of the structure is flung open and a madman wearing a skull mask and crimson robe enters. This is the Crimson Ghost, and the men deliberating over the robbery work for him. The Crimson Ghost is determined to get his hands on the Cyclotrode. The Cyclotrode cannot only stop nuclear missiles, but it can also cripple transportation and communications. The Crimson Ghost wants the invention for his own nefarious plans, including selling the device to foreign powers.

Two people know of the Crimson Ghost’s dangerous ambitions, and they are criminologist Duncan Richards and Diana Farnsworth, secretary for the professor who created the Cyclotrode. The duo is determined to stop the villain and his henchmen from taking the contraption and destroying lives.

Throughout the twelve-part serial named after the blackguard the Crimson Ghost, the duo matched wits and fists with the miscreant and his aides in an attempt to keep the Cyclotrode from being used for mass destruction. Duncan and Diana were threatened with death by explosion, poison gas, deadly slave collars, and death rays. Each of the episodes in the serial ended with a cliffhanger: a car plummeting over a cliff, a fire started leaving the heroes only moments to save the day, if at all, or a train bearing down on innocent parties.

The Crimson Ghost was just one of several “cliffhanger” serials produced by Republic Pictures that enticed audiences to return to the theater again and again to see if the heroes of the story won out or if the bad guy succeeded in thwarting attempts to put a stop to his diabolical intensions to obliterate mankind.

Republic’s stock and trade were cliffhanger serials—science fiction, mysteries, and the ever popular horror genre. Nat Levine, founder of Mascot Pictures and later a much-maligned executive working for Herbert Yates, is credited with the production of a cliffhanger. Writer, journalist, and film historian Ephraim Katz defines a cliffhanger as an adventure serial consisting of several episodes, each of which ends on a suspenseful note to hold the audience in expectation of the next.

Levine made a number of silent-film chapter plays that brought return business to the movie houses. One of the first was Isle of Sunken Gold. Produced in 1927, the adventure picture was about a sea captain who had half a map leading to a treasure buried on an island in the South Sea. The ruler of the island, a beautiful princess, had the other half of the map, and the two joined forces to battle a gang of pirates and a group of islanders who didn’t want anyone to get the treasure.

At Republic, Levine continued to create cliffhangers that excited and confounded moviegoers.

To learn more about the many films Republic Pictures produced read

Cowboys, Creatures and Classics: The Story of Republic Pictures