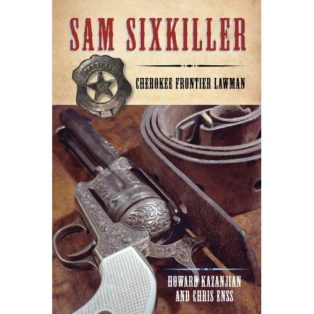

Enter to win a copy of

Sam Sixkiller: Frontier Cherokee Lawman

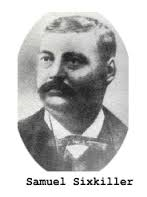

The sweeping prairie lay quietly under the heat of a brassy sun as a lone wagon topped a grassy knoll that afforded an arresting view from every direction. Redbird Sixkiller drove the team of two horses pulling the wagon toward the town of Tahlequah, Oklahoma Territory, in the near distance. His four-year-old son, Sam, sat beside him captivated by the sights and listening intently to the stories Redbird told about his ancestors and the origin of the Sixkiller family name. Redbird shared with Sam a tale about one of their fearless relatives. The ancestor was engaged in battle against the Creek Indians and had killed six braves and then himself before another band of hostile Creek Indians that surrounded him could attack. The Cherokee Indian warriors who witnessed the daring act referred to the warrior as Sixkiller.

Given the courageous example Sixkiller had set, Redbird felt he owed it to the legendary Cherokee to face with the same fortitude the trials that lay ahead for the Indian Nation. It was a pathetic group of thousands of Indians who were herded west during the winter of 1838–39. Redbird Sixkiller’s recollection of the grueling journey that came to be known as the Trail of Tears was passed along to his son, his son’s sons, and every generation that followed. The January 18, 1972, edition of the Statesville, North Carolina, newspaper, the Statesville Daily Record, published Redbird’s reminiscences as told by those generations and noted that the inhumanity of the forced move of the Indians preyed on his sense of justice. He saw helpless Cherokee arrested, dragged from their homes, and driven at bayonet point into the stockades. He watched as his people were loaded like cattle into wagons and hauled west. Redbird told Sam how few of the Indians were given time to make arrangements to leave and that one family was driven from its home as members were preparing to bury a child who had died. He recounted how another mother forced from her home fell and died of a heart attack before they could take her to the stockade. Still another mother died of pneumonia contracted after giving her only blanket for the protection of a sick child.

Sam listened intently to his father describe a Cherokee elder’s reaction to the tragic event. The elder’s name was Chief Junaluska. During the Battle of the Horse Shoe, the chief saved the life of a man who would eventually become the president of the United States, and who would support the relocation of Indian tribes. The chief later admitted that if he had known the life he was saving was that of Andrew Jackson, American history would have been written differently.

Like many other Indians who survived the Trail of Tears, Redbird passed on to his son the stories of how government soldiers treated the Cherokee during this time. Only a few men were remembered for being humane. The majority of officers and the members of their units treated the Indians harshly. A soldier with the Georgia volunteers who showed sympathy to the Cherokee described in his memoirs the severity of the treatment the Indians received. “I fought through the War Between the States,” the veteran recounted, “and I have seen men shot to pieces by the thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.”

To learn more about Sam Sixkiller read:

Sam Sixkiller: Frontier Cherokee Lawman.