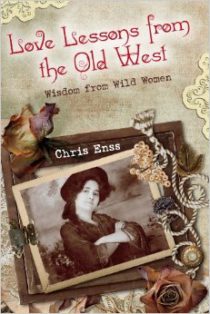

Enter to win a copy of

Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women.

Maria Josefa Jaramillo was fifteen when she married well-known frontiersman Kit Carson on February 3, 1843. The thirty-three year old Carson made Maria’s stomach flutter with excitement. He was fearless and decent and in him she saw forever.

Maria Josefa was born on March 19, 1828, in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Her father, Francisco Jaramillo, was a merchant, and her mother, Maria Apolonia Vigil, owned substantial acreage in the Rio Grande area of the state. Maria Josefa helped her parents maintain their ranch and cared for her younger brothers and sisters. She met Carson in Taos in 1842. He had been on an expedition with Colonel John Charles Fremont in the Rocky Mountains and was anxious to visit a place where there were lots of people.

Although Maria Josefa and Carson were equally impressed with one another, her father would not permit them to marry because Carson was illiterate. Francisco was an educated man and very well respected in the community. He was aware of Carson’s work as an accomplished scout, criss crossing the western territories, but preferred his daughter marry someone with a scholastic background, at the very least someone who was a member of the Catholic faith. Carson was determined to make Maria Josefa his wife and decided to convert to Catholicism. He attended the necessary classes, counseled with a priest, and paid the fee required for a wedding ceremony in the church.

A short three months after the wedding, Carson left on the first of many expeditions he would participate in during his married life. Carson had been leading treks to various parts of the unsettled frontier since he was fifteen years old. He was born in Madison County, Kentucky, on December 24, 1809. Just after his first birthday his parents moved to Howard County, Missouri. Carson had five brothers and six sisters. His father was a lumberjack and died in a work related accident when Carson was nine years old. At the age of fourteen he was an apprentice to a saddle maker, a job which he said “soon became irksome to him.” He ran away (a one cent reward was offered for his return) and arrived in Santa Fe in the fall of 1826.

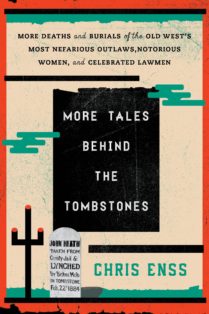

To learn more about Maria Josefa Carson and the other incredible women on the frontier read

Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women.