Enter to win and pick a book you’d like to have from the author’s catalog.

Author’s favorite: Thunder Over the Prairie.

The gripping tale of a murder in Dodge City

in 1878―and how legendary lawmen chased down the killer

A New York Times Bestseller! “No women need apply.” Western towns looking for a local doctor during the frontier era often concluded their advertisements in just that manner. Yet apply they did. And in small towns all over the West, highly trained women from medical colleges in the East took on the post of local doctor to great acclaim.

Stories of the bandits, cattle rustlers, horse thieves, and highwaymen of the Old West have intrigued readers since the first pioneers ventured across the plains. More than 125 years after outlaw Jessie James made a famously candid statement about the public’s continuing interest in criminals, people continue to be drawn to the tales of the desperadoes who roamed the wild frontier. As Jesse aptly commented in 1879, “All the world likes an outlaw. For some damn reason they remember them.”

A lawless element followed the daring collection of prospectors, hard-working emigrant men and women, and enterprising farmers to the gold fields of California. While civilized pioneers were building churches, schools, theaters, and hotels, thieves and outlaws were terrorizing camp followers, looting mining claims, and robbing Wells Fargo stagecoaches.

Where liquor ran freely, it seemed so did crime. Alcohol often eroded away any effort ambitious sojourners painstakingly made to tame the rowdy territory. Drunkenness, banditry, and violence plagued the California boomtowns, provoking frightened citizens to take the law into their own hands, or appoint willing, but unqualified, peace officers to act on their behalf.

Many of the outlaws who dominated sections of the rugged territory were desperate men who were once honest members of the community, but who felt forced by circumstances into a life of evil. In the later part of the 1860s, a majority of the offenders were veterans of the Civil War, ex-Confederate soldiers like Cole Younger, Frank Dalton, and Ben Thompson, who were convinced they no longer had a country of their own, or a choice but to become a criminal.

Outlaw Tales of California contains the tales and adventures of the most famous rebels and brigands in California’s history. Listed among the wanted men of long ago are Black Bart, the notorious highwayman who rarely left the scene of a crime without leaving a poem behind; John Allen, the barber turned horse thief also known as Sheet-Iron Jack; and the most feared bandit of all, “Bloody” Joaquin Murieta.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

Rain dripped steadily from the bare trees outside the dark parlor. The bride stood at the top of the stairs, a red rose sent from her best friend pinned inside her dress. Unveiled, she started down the steps to the man who waited to marry her.

She had resisted his courtship and insisted that marriage did not fit her plans. The young engineer standing at the foot of the staircase had made his own plans. He arrived out of the wild West with a “now or never” declaration. He had taken off his large hooded overcoat, placed his pipe and pistol on the bureau in the room that had belonged to the bride’s grandmother, and the quiet force of his intent carried the day.

The bride well knew that the Quaker marriage ceremony puts the responsibility for making the vows directly on those who must keep them. She descended the stairs, catching sight of her parents, a handful of other family members, her best friend’s husband, and the man she had finally agreed to marry.

Mary Hallock gripped the arm of Arthur De Wint Foote and stepped up in front of the assembly of Friends, as the Quakers called themselves, to speak those irrevocable vows. She was twenty-nine, with an established career as an illustrator for the best magazines of the day. She had carefully considered what she would give up by taking this step. Arthur was a mining engineer, and his work was in the West. She was an artist, and all her contacts were in Boston and New York. She faced forward with a mixture of anxiety and joy.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

Petite Nellie Pooler Chapman stood on the red velvet covered riser and gazed inside the mouth of a burly, distressed miner and shook her head. She would have to remove the tooth that was causing the prospector so much pain. Nellie selected a corkscrew type instrument to begin the process. She wrapped the tool around the tooth and with considerable effort wrenched it out of the man’s mouth. The relief he felt was almost instantaneous.

Nellie Pooler Chapman was the first licensed dentist in the Old West and over her 30 year career would care for numerous residence in Nevada County, California. She was born in Norridgewock, Maine in 1847 and at the age of 13 relocated with her parents to the Gold Country. There she met and married Dr. Allen Chapman, a prominent dentist in the area. The parlor in the home he built for his new bride included a dental office.

Nellie did not enter the field of dentistry eagerly. She assisted her husband in his work, but was not initially interested in the job as a career. It wasn’t until she had spent years learning about the profession from Allen that she decided to apply for a license of her own. Nellie became a full-fledged dentist in 1879. She was the first woman to be registered in the field in the western territories. When her husband decided to open an office in Virginia City, Nevada, Nellie was the sole dentist between Sacramento and Donner Lake.

Dr. Chapman outfitted her thriving practice with a porcelain bowl, crystal water glasses and the most modern drills and aspirators. The chair her patients sat in was covered in red velvet and labeled “Imperial Columbia” in gold script.

In 1897, Nellie’s husband passed away. She continued on with the practice for another 9 years, providing care for Northern California residence.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

There before her was a panoramic view of the snow-capped Sierra peaks-jagged an folded, thrusting upward from steep, forested hills-taller than what they called mountains in the East. The California sky was a blue vault overhead. The sun, she noted, was at the perfect angle to highlight the features of the rugged landscape for her camera.

Eliza Withinton pulled away the skirt-tent wrapped around her bulky camera and tripod, reversed the lenses she’s turned into the camera box, reset the screws, and anchored the contraption in the rocky soil of the Amador County foothills. Propping her black linen parasol against the tripod, she carefully unwrapped a sensitized glass plate from the damp towel in which it had been carried to the distant foothills, slipped it into place and exposed the plate.

The camera, covered with one of her heavy, black dress skirts, then became her darkroom. Eliza slipped beneath the negative, then washed and replaced the glass in the plateholder for a more convenient time to fix and varnish the picture.

Packing her precious equipment, she scrambled back down the steep, rocky trail to the dusty road, using her cane-headed parasol for a walking stick. There she waiting for a fruit wagon to return and carry her back to Ione City and the appointments for portraits at her studio.

Eliza Withington described how she photographed the Sierras in an article for the Philadelphia Photographer in 1876. “How a Woman Makes Landscape Photographs” detailed her methods of working in the field. The article provided a complete description of her equipment, how she packed it to survive torturous overland skirts, shawls, and parasol to process her five-by-eight-inch glass plates in the field.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

Frontier pioneer Eliza Inman wrote in her journal in 1843, “If Hell laid to the west Americans would cross Heaven to reach it.” Luzena Stanley Wilson, mother of three and wife of aspiring gold miner, Mason Wilson, wholeheartedly agreed with the sentiment. In 1849, news of the Gold Rush captivated Mason’s imagination and he moved his family from their home in Missouri to a mining town west of the Rockies.

Shortly after arriving in Nevada City, California, Mason left Luzena alone with the children to make her while he staked out a gold claim. Luzena quickly went to work unpacking, making beds, and firing up her stove. As she worked she contemplated how she was going to help make good on the cost it took to transport her family to the area. “As always occurs to the mind of a woman, I thought of taking in boarders,” she wrote in her journal. “So I bought two boards from a precious pile belonging to a man who was building the second wooden house in town. With my own hands I chopped stakes, drove them into the ground, and set up my table. I bought provisions from a neighboring store, and when my husband came back at night he found, mid the weird light of the pine torches, twenty miners eating at my table. Each man as he rose put a $1 in my hand and said I might count him as a permanent customer.”

Within six weeks of opening her business, Luzena had earned enough to pay back the money Mason had borrowed to move his family to the Gold Country. She also expanded and renovated the make-shift hotel and purchased a new stove. By the end of the summer in 1850, Luzena had an average seventy five to two hundred boarders living at the establishment, each paying $25 a week.

Mason never did find the mother lode, but Luzena became one of the most prosperous women in the territory. Mason struggled with Luzena’s success for a long while before he left her and the children.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

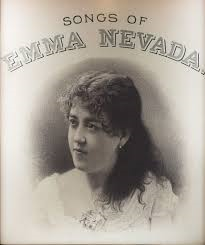

Doc Wixom lifted his three-year-old daughter and stood her carefully in the middle of a table. Wrapped in an American flag, golden brown ringlets framing her sweet face, Emma Wixom smiled at her audience. The church on the banks of Deer Creek was crowded with miners and merchants, teamsters and saloonkeepers. They were there to benefit a local charity, and the sight of a child symbolized the hopes of the future.

Unafraid of the eager faces crowed around the table, little Emma Wixom knew what was expected of her. She was happy to sing on this lovely morning. She did it all the time, unaccompanied, singing for the pure love of the sound.

That summer day in 1862, in the thriving California Gold Rush town named Nevada, she gave a performance to remember. Inside the Baptist church on the banks of Deer Creek, Emma took a deep breath and released a pure soprano voice that held the audience spellbound. By the time the last note sounded, there was not a dry eye in the house. Brawny, wet-cheeked miners showered her with nuggets of pure gold.

Emma Wixom, the daughter of a country doctor, began a long and illustrious career that day in the church. She would go on to sing opera in Europe and America. She would draw standing-room-only crowds to her performances, but her biggest fans remained the reckless, rugged gold miners who first took a little child into their hearts.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

Dutch Carver, a half-drunk gold miner, burst into Eleanora Dumont’s gambling house and demanded to see the famous proprietor. “I’m here for a fling at the cards tonight with your lady boss, Madame Mustache,” Carver told one of the scantily-attired women draped across his arm. He handed the young lady a silver dollar and smiled confidently. “Now you take this and buy yourself a drink. Come around after I clean out the Madame and maybe we’ll do a little celebrating.” The woman laughed in Dutch’s face. “I won’t hold my breath,” she said.

Eleanora Dumont soon appeared at the gambling table. She was dressed in a stylish garibaldi blouse and skirt. Her features were coarse and there was a growth of dark hair on her upper lip. At one time she had been considered a beautiful woman, but years of hard frontier living had robbed her of her good looks. It had not, however, taken away her ability to play poker. She was the first and best lady card sharp in California. Her skills had only enhanced with age.

Eleanora sat down at the table across from Dutch and began shuffling the deck of cards. “What’s your preference?” she asked him. Dutch laid a wad of money out on the table in front of him. “I don’t care,” he said. “I’ve got more than two hundred dollars. Let’s get going now, and I don’t want to quit until you’ve got all my money, or until I’ve got a considerable amount of yours.”

Eleanora told him that she preferred the game vingt-et-un (twenty-one or blackjack). The cards were dealth and the game began. In a short hour and a half Dutch Carver had lost his entire bankroll to Eleanora.

When the game ended the gambler stood up and started to leave the saloon. Eleanora ordered him to sit down and have a drink on the house. He took a place at the bar and the bartender served him a glass of milk. This was the customary course of action at the Twenty-One Club. All losers had to partake. Eleanora believed that “any man silly enough to lose his last cent to a woman deserved a milk diet.”