- 1882 Circus owner PT Barnum buys his world famous elephant Jumbo

Hearts West

Enter now to win a copy of

Hearts West: True Stories of Mail-Order Brides on the Frontier

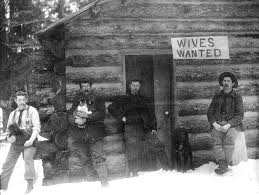

The promise of boundless acres of land in the West lured hundreds of men away from farms, businesses, and homes in the eastern states as tales of early explorers and fur trappers filtered back from the frontier. Thousands more headed for California after hearing the siren call of Gold! Tracts of timber in the Northwest and a farming paradise in the Willamette Valley of Oregon had even more people packing up and leaving home for the promised land.

The vast acres and the trees and the gold were all there, and men set about carving their place in the wilderness. By the early 1850s, western adventurers lifted their heads and looked around and realized one vital element was missing from the bountiful western territories: women.

“A woman’s track was discovered in the road leading to Mormon Island. The track of a woman was such a novel thing the boys enclosed it with sticks (you know women were scared in California in those days), sang, danced, telling yarns and giving cheers to the woman’s track in the dust until a late hour in the evening,” recalled Henry Bigler, third governor of California.

Eliza Farnham, recognizing that she was no beauty, nevertheless was astonished to be the target of admiring eyes wherever she went in the Gold Country in 1849. Shocked at the dissolute lives of the largely male inhabitants of California, she conceived a plan to bring proper ladies to the West, which she saw as badly in need of the civilizing hand of women. Her plan included a rigorous application process to guarantee only the most virtuous ladies would arrive on the good ship Angelique. The plan was widely publicized and endorsed by clergymen and officials. With anticipation running high, hundreds of angry bachelors nearly started a riot when just three ladies tiptoed down the gangplank in San Francisco.

In Washington Territory, where men outnumbered women nine to one in the 1850s and 1860s, a scheme to ship respectable women and families to the shores of Puget Sound was hatched by Asa Mercer. He raised money for the first trip, traveled to the eastern seaboard, and in 1864 brought his first shipload of marriageable women to Seattle. Only eleven women disembarked, leaving a lot of disillusioned bachelors. Mercer’s second trip in 1866 netted a larger cargo of potential brides, but the trip was to be his last attempt at supplying a rather urgent demand.

To learn more about Mercer’s Maids and other mail order brides read Hearts West.

This Day…

- 1898 1st auto insurance policy in US issued, by Travelers Insurance Co

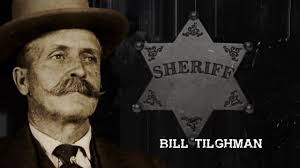

The Tale Behind Bill Tilghman’s Tombstone

Last chance to enter to win a copy of More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

Lynn died in a gun battle with Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation agent Crockett Long in Mandill, Oklahoma. On July 17, 1932, an inebriated Lynn confronted Agent Crockett with his pistol drawn. The agent quickly drew his weapon, and the two fired at one another at the same time. Both Agent Crockett and Wi“He died for the state he helped create. He set an example of modesty and courage that few could match, yet he made us all better men for trying.”

— Governor Martin E. Trapp speaking at the funeral of Bill Tilghman

Legendary lawman and sportswriter Bat Masterson once referred to his well-known colleague Bill Tilghman as “the finest among us all.” Marshall Tilghman and Sheriff Bat Masterson were two members of the “most intrepid posse” of the Old West, a group of policemen who, in 1878, tracked down the killer of a popular songstress named Dora Hand.

William Matthew Tilghman, Jr.’s drive to legitimately right a wrong began at an early age. He was born on the Fourth of July 1854 in Fort Dodge, Iowa. His father was a soldier turned farmer, and his mother was a homemaker. Bill spent his early childhood in the heart of the Sioux Indian territory in Minnesota. Grazed by an arrow when he was a baby, he was raised to respect Native Americans and protect his family from tribes that felt they had been unfairly treated by the government. Bill was one of six children. His mother insisted he had been “born to a life of danger.”

In 1859 his family moved to a homestead near Atchison, Kansas. While Bill’s father and oldest brother were fighting in the Civil War, he worked the farm and hunted game. One of the most significant events in his early life occurred when he was twelve years old while returning home from a blackberry hunt. His hero, Bill Hickok, rode up beside him and asked if he had seen a man ride through with a team of mules and a wagon.

The wagon and mules had been stolen in Abilene, and the marshal had pursued the culprit across four hundred miles. Bill told Hickok that the thief had passed him on the road that led to Atchison. The marshal caught the criminal before he left the area and escorted him back to the scene of the crime. Bill was so taken by Hickok’s passion for upholding the law that he decided to follow in his footsteps and become a scout and lawman.

From 1871 to 1888, Bill hunted buffalo, rounded up livestock, scouted for the military, and operated a tavern in Dodge City, Kansas. In 1889, Bill settled in Oklahoma and was at once appointed deputy United States marshal, thus taking to a calling that made him famous as a hustler of outlaws of the most desperate kind. During his term in office, he amassed a fortune in rewards paid by the government for the capture of such noted desperados, train robbers, bank robbers, and murderers as Bill Doolin, Tulsa Jack, Bitter Creek, and Bill Dalton.

In his many years of continuous service as United States marshal, Bill was the associate of such noted scouts as Luke Short, Pat Garrett, Wild Bill Hickok, Neal Brown, and Charley Bassett. Bat Masterson was also one of the famous marshals of Dodge City in the early days and knew Bill Tilghman well. The two were lifelong friends. Masterson once said of Tilghman, “After a career of sixteen years on the firing lines of America’s last frontier and after being shot at five hundred times by the most desperate outlaws in the land, whose unerring aim with a six-shooter or Winchester seldom failed to bring down their victims, this man, Bill Tilghman, came through it all unscathed, and is perhaps the only frontiersman who has been constantly on the job for more than a generation and lives to tell the tale.”

Bill Tilghman was twice elected sheriff of Lincoln County, Oklahoma, after which he was elected to the state senate, resigning that office to accept the job of chief of police of Oklahoma City. He would resign that position in 1914 to campaign for United States marshal in Oklahoma. Bill received the appointment and rendered valuable service not only during that term but also at various other times he had the post.

In 1924 Bill was persuaded to take on the job of cleaning up a lawless oil boomtown called Cromwell in Oklahoma. He was seventy-one years old when he was shot in an ambush on Saturday, November 1, 1924, by a corrupt Prohibition enforcement officer. Wiley Lynn, the man who shot the aged officer, fled the scene of the crime but gave himself up to authorities in Holdenville, Oklahoma. Lynn admitted to officers at Holdenville that he shot Bill, but would make no further statement. He was placed in the Hughes County jail to await formal action by the authorities.

Cromwell had long been known as a “wide open” town. Dance halls and gambling joints had been running freely, and booze was easy to obtain. Vice conditions were regarded as so bad that federal authorities had been dispatched to the area. Lynn was one of a handful of agents sent to the territory.

Conditions in Cromwell did not get any better with the presence of the federal authorities. When the situation escalated, a step toward more law enforcement was made, and Bill was called in to serve in the role in which he had gained fame. Now he no longer was the Bill of the old days when his daring speed on the trigger made him respected and feared by all law breakers. Conditions improved somewhat, however, and there were indications that a complete cleanup there might be made.

The fatal shooting occurred when Bill attempted to place under arrest members of a motorcar party who were disturbing the peace on the main street of town. One of the men fired a pistol shot into the air, and a few minutes later spectators heard angry words and another shot. Bill fell and was dead before anyone reached him.

After shooting Marshal Tilghman, the slayer fled in the car, occupied by another man and two women, and drove rapidly out of town. Wiley Lynn was arrested and tried for killing Bill but was found not guilty of murder. The jury believed he had acted in self-defense.

Eight years after killing Marshal Tilghman, Wiley ley Lynn died as a result of gunshot wounds.

Graveside services for lawman Bill Tilghman were held at Oak Park Cemetery in Lincoln County, Oklahoma.

To learn more about the deaths of legendary western characters read

More Tales Behind the Tombstones:

More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

This Day…

The Tale Behind Stephen Foster’s Tombstone

Enter now to win a copy of More Tales Behind the Tombstones:

More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

“Now the nodding wild flow’rs may wither on the shore. While her gentle fingers will cull them no more. Oh! I sigh for Jeannie with the light brown hair. Floating like a vapor, on the soft summer air—from “Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair” by Stephen Foster

Songwriter and composer Stephen Collins Foster was lying face down in a pool of his own blood when a housekeeper at a cheap New York boarding house found him on the morning of January 13, 1864. The man who had penned such popular tunes as “Oh! Susanna” and “Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair” collapsed from a fever while walking to a wash basin to get some water. He struck his head on the porcelain bowl and cut a large gash in his face and neck. He was taken to Bellevue Hospital where he was pronounced dead.

Stephen Foster was born on July 4, 1826, in Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania. He was the youngest of eleven children and from an early age displayed exceptional musical talent. At seven years old his parents gave him a flageolet, a sixteenth-century woodwind instrument. Within a short time, Stephen mastered the flute-like whistle and expanded his abilities to include harmonica, piano, and guitar. Although his talent captivated family and friends, he did not have a desire to perform. Stephen preferred to write and wanted to study music as a science.

In 1841, Stephen’s mother hired a tutor to teach her son the fundamentals of music as well as how to speak French and German. Stephen composed his first published song, entitled “Open Thy Lattice Love,” in 1842 at the age of seventeen. A short time later he moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, and took a job working for his brother as an accounting clerk. He wrote many more songs during this time, all of which were published, but the money he received for his work was next to nothing.

By 1850, he decided to abandon the accounting business and devote himself full-time to writing music. His gift for harmony and poetry led to the creation of such well-known tunes as “Camptown Races” and “My Old Kentucky Home.” During this time, he met Jane McDowell, the daughter of a physician from the Pittsburgh area. The two fell in love and were married on July 22, 1850. Stephen continued writing songs that were published and well received, but he realized very little financially for his music at the onset of his career because he allowed his work to be published without thought of compensation. He earned $15,000 for the song “Old Folks at Home,” and many of his other tunes were equally as profitable. Unfortunately, multiple publishers often printed their own competing editions of Stephen’s songs, paying him nothing and eroding any long-term monetary benefits.

Stephen’s struggles with managing his money and the loss of his parents as well as many of his siblings in a short time period proved more than he could bear. Consequently, he sought comfort in drinking. The alcohol soon became all-consuming and quickly became an issue in his marriage. Stephen became addicted and after numerous ultimatums and attempts to get him to stop drinking, Jane decided to take their daughter back to her parents’ home in Pittsburgh.

Stephen sank into a deep depression and continued drinking. He spent all his income on alcohol, and when he ran out of money, he sold his clothing to buy more to drink. He wore rags and went days without eating. His brothers and sister would step in to help, but Stephen would not and could not change. On Saturday evening, January 9, 1864, the thirty-seven-year-old man passed out in a drunken stupor in his hotel room. When he awoke, he was violently ill from liver failure and in his weakened condition he fell and hit his head.

Stephen’s wife Jane and one of his brothers came to the hospital to claim his body. Nurses gave his family his clothes along with 38 cents that were found in his pocket and a scrap of paper upon which he had written the words, “Dear Friends and Gentle Hearts.”

He was buried in Alleghany Cemetery in Pittsburgh, beside his mother. Upon his plain marble headstone is the simple inscription: “Stephen Foster of Pittsburgh. Born July 4, 1826. Died January 13, 1864.”

To learn more about the deaths of the legendary characters of the

Old West read More Tales Behind the Tombstones.

This Day…

| 1878 – The first telephone switchboard was installed in New Haven, CT. |

The Tale Behind John Chisum’s Tombstone

Enter now to enter to win a copy of More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

“No matter where people go, sooner or later there’s the law. And sooner or later they find God’s already been there.”

—John Wayne as John Chisum in Chisum (1970)

Cattle barons of the vast frontier such as John Chisum once held undisputed sway over the great public domain. He ruled like a lord of old over the Pecos country in New Mexico where desperate battles were fought between rival cattle barons for more grazing land.

Rancher John Simpson Chisum was born into an affluent family in Tennessee on a plantation on August 16, 1824. His parents relocated their five children to Red River County, Texas, in 1837. John was thirteen when his family settled in Paris, Texas. He worked a series of odd jobs before becoming the county clerk in 1852.

At the age of thirty, John ventured into cattle ranching with Stephen K. Fowler, a businessman from New York. The Half Circle P brand, owned by Chisum and Fowler, was seen on livestock across a great expanse of the land John purchased in Denton County, Texas. Stephen’s original investment of $6,000 resulted in a $100,000 profit in ten years.

Chisum used his portion of profitable shares to buy more land and cattle. In addition to running his own spread, which included five thousand head of cattle, John also managed livestock for other ranchers and ambitious investors. By 1861, John Chisum was recognized as one of the most important cattle dealers in North Texas.

When the Civil War started, John contracted with the military to supply beef to soldiers in the Trans-Mississippi Confederate Army Department. After the war he drove his cattle into eastern New Mexico to sell to the government for the cavalry and the Indian reservations. In 1867, John moved his base of operation to Roswell, New Mexico, where he already had more than one thousand head of cows. He established a series of ranches along a 150-mile stretch of the Pecos River. John’s empire grew to eighty thousand head of cattle and he hired more than one hundred cowboys to work the livestock.

John Chisum was involved tangentially with the Lincoln County Range War in 1878. The dispute initially began as a fight between cattlemen and two store owners over who rightfully controlled the trade of dry goods in the county. Cattlemen John Tunstall and his business partner, Alexander McSween, owned one of the stores, and they were being threatened by the owners of the competing establishment who had an economic stranglehold on the area. Each store owner organized his own men to protect his enterprises and homes from being overrun. Tunstall and McSween had in their employ Billy the Kid and his associates. John Chisum supported Tunstall’s efforts. His exact role in the dispute is unknown.

After Tunstall was murdered, Billy the Kid took Chisum to task over money he insisted John owed him for protection. Chisum disagreed, and Billy resented him for it. In 1880, Chisum helped get Pat Garrett, the sheriff who shot Billy the Kid, elected to office.

John Chisum’s cattle operations continued to thrive, and he shared his good fortune with his brother, James. John gave James his own herd of cattle to manage.

John contracted throat cancer in late 1883 and had surgery to remove the growth in 1884. He died on December 22, 1884, in Eureka, Arkansas, where he had been recuperating from the operation. His giant cattle empire was worth $500,000. Chisum never married, but it is believed he fathered two children with one of the slave women he owned named Jensie.

John Chisum’s body was laid to rest in Paris, Texas. He was sixty years old when he passed away.

To learn more about how some of the Old West’s most legendary characters died read More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

This Day…

The Tale Behind Seth Bullock’s Tombstone

Enter to win a copy of More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

“[Seth Bullock is a] splendid-looking fellow with his size and subtle strength, his strongly marked, aquiline face with his big mustache, and the broad brim of his soft hat drawn down around his hawk eyes.”

—President Theodore Roosevelt

It wasn’t a bullet from an outlaw’s six-shooter or an enemy soldier in the Spanish-American War that claimed the life of one of the fiercest lawmen in the history of the Dakotas. Seth Bullock died of colon cancer. The accomplished businessman, rancher, politician, and lawman suffered with the disease for years and he died in September 1919 at the age of sixty-two. Born in Amhertberg, Ontario, Canada, in August 1876, six decades later he was remembered for his strength of character as well as the influence he had on the wild frontier.

According to the September 28, 1919, edition of the Kansas City Star, before Seth Bullock made his mark on the Black Hills of Dakota, he was a pioneer in Montana. He was the first sheriff in Helena, Montana, and a member of a famous vigilance committee that rid the region of a desperate band of horse thieves.

Upon hearing that gold had been discovered in the Black Hills, Seth and some of his friends decided to go to that area of the country in the summer of 1876. In March 1877, he became Lawrence County, Dakota’s first sheriff. The gold camp contained some of the most notorious, cutthroat criminals in the country. Many were intimidated by the lawman.

Seth dressed like a minister, had the stare of a mad cobra, and was silent as a confidential clerk working for Rockefeller. In the beginning, his ability to effectively do his job in Lawrence County was challenged by an outlaw who intensely disliked the lawman. He gave orders that Seth should leave the camp and never return. The man threatened to shoot Seth if he didn’t go. After being warned by friends, the sheriff borrowed a squirrel gun from an old hunter and proceeded down the street to the saloon where the desperado was waiting. When the man saw Seth unafraid and coming right for him, he backed down and fled the scene.

As a representative of law and order, the Dakota lawman tracked down a number of stage robbers, gamblers, and murderers, and, according to the October 1, 1919, edition of the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, killed more than twenty-five lawbreakers who refused arrest.

In addition to his career in law enforcement (Seth also served as a United States marshal in Western Dakota Territory) he co-owned and operated a hardware store and warehouse in Deadwood with his business partner Sol Star. It was one of the most prosperous companies in the Black Hills.

Seth met Theodore Roosevelt in 1884. Roosevelt was a deputy sheriff in Medora, North Dakota, and had tracked a criminal to Seth’s jurisdiction. The two lawmen became fast friends. He became one of Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War and was named captain of one of the future president’s troops.

Seth was an elected representative to the Senate and introduced the resolution to set aside Yellowstone as a national park. He was the first forest supervisor of the Black Hills and the cofounder of the mining town Belle Fourche.

Seth was serving his third term as United States marshal for the District of South Dakota when he was diagnosed with cancer. Friends and family noted that in spite of his health he refused to be complacent. He continued on with his work regardless of the debilitating illness.

When President Roosevelt died in January 1919, Seth decided to erect a monument in his friend’s honor. He oversaw the building of a stone tower known as Mount Roosevelt on Sheep Mountain located five miles from Deadwood. The tower was completed in June 1919. Seth died on September 23, 1919, at his home surrounded by his loved ones. He was buried at Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood. His grave faces Mount Roosevelt.