1873 – A group of Modoc warriors defeats the United States Army in the First Battle of the Stronghold, a part of the Modoc War

The Tale Behind Elizabeth Blackwell’s Tombstone

Enter now to win a copy of More Tales Behind the Tombstones:

More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

“A lady, on his invitation, entered, whom he formally introduced as Miss Elizabeth Blackwell. A hush fell upon the class as if each member had been stricken with paralysis. A death-like stillness prevailed during the lecture, and only the newly arrived student took notes.”

—1911 recollection by a former classmate of Elizabeth Blackwell

On Wednesday, January 25, 1911, physicians across the world gathered at the great hall at the Academy of Medicine in New York to honor America’s first woman doctor, Elizabeth Blackwell. The tenacious pioneer in the fight for the right of women to study and practice medicine had died nine months prior to the event honoring the contributions she made to the field. The audience was composed largely of women, all of whom owed a debt of gratitude to Elizabeth Blackwell.

Born in Bristol, England, on February 3, 1821, Elizabeth immigrated to America in 1832 with her parents. Her desire to attend school and study medicine began at an early age. Elizabeth was twenty-six years old when she was admitted to New York’s Geneva College in 1847. She had applied to twenty institutions before being accepted as a medical student at the prestigious university. The male students there believed Elizabeth’s request was a joke and agreed to tolerate her presence in class, but the daring young woman was not playing around. She prevailed and triumphed over taunts and bias while at school to earn her degree only two years after enrolling.

While in her last year of school, she treated an infant with an eye infection. As she was washing the baby’s eye with water, she accidentally splattered the contaminated liquid in her own eye. Six months later she had the eye removed and replaced with a glass eye. Hospitals and dispensaries refused to admit her to practice at their facilities because of her partial blindness, and she was denounced by the press and from the pulpit because she was a woman who dared to practice medicine.

After graduating in 1849, Elizabeth found herself socially and professionally boycotted. Public sentiment was so against her for pursuing a career in a field deemed unladylike that she could not find a place to live anywhere in New York. Using funds given to her by her family, she built her own home in New York City.

In 1854, she borrowed the capital needed to build a small dispensary for women in the country. Most of the patients she worked with were poor. Patients were charged a mere $4 a week for services that would cost them $2,000 at another facility. Elizabeth also founded the Women’s Medical College of New York, and, when the Civil War broke out, she assisted in launching the Sanitary Aid Association. The Sanitary Aid Association was established to promote hygiene and campaign for better preventive medicine. In addition to maintaining her practice and creating benevolent community services, Elizabeth wrote a number of books on the subject of medicine. Two of her most popular titles were Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession for Women and Essays in Medical Sociology.

By the turn of the century, Elizabeth Blackwell had retired from medicine and returned to England. In the spring of 1907, she was injured in a fall from which she never fully recovered. She died on May 31, 1910, from a stroke. The epitaph below the Celtic cross which marks her grave at Kilmun Churchyard on the Holy Loch, near Clyde, includes these words: “The first woman in modern times to graduate in medicine (1849) and the first to be placed on the British Medical Register (1859).” Elizabeth’s courage and determination led the way for many other women to enter the field of medicine and several of those women traveled west to work in their chosen profession and bring healing to the frontier.

To learn more tales behind the tombstones read

More Tales Behind the Tombstones:

More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

This Day…

1897 – M H Cannon becomes 1st woman state senator in US (Utah)

Chalk Beeson’s Tale

Enter now to win a copy of

More Tales Behind the Tombstones

More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

“He came to Dodge City when every man carried a gun, and the fittest survived. Beeson survived. But he is not fierce. He has not shot a man in several days.”

—Dodge City, Kansas, newspaper

Well-known Dodge City, Kansas, lawman and politician Chalk Beeson claimed he “drank bullets in his coffee for breakfast.” Few doubted how tough Sheriff Beeson was—particularly desperados raising hell in Ford County, Kansas.

Born in Salem, Ohio, in 1876, the highly esteemed man had a reputation for tracking even the most wanted criminals until they were caught. In November 1892, Chalk decided to ride into the Oklahoma Territory on his own to capture the notorious Doolin Gang. The gang had robbed the Spearville Ford County Bank in broad daylight and Chalk was not going to let them get away with it.

According to the August 12, 1912, edition of the Hutchinson, Kansas, newspaper the Hutchinson News, Chalk was so provoked by the Doolin Gang’s actions that he refused to wait until a posse was formed before he took out after the bandits. “He went to Oklahoma under an alias,” the newspaper article read, “and when he found the headquarters of the gang near Ingalls, he went to Guthrie and was appointed a deputy United States marshal, as he was far out of his jurisdiction as sheriff.”

One particular man in the gang Chalk was determined to arrest was Oliver Yantes, who was living with a woman in a cabin five miles from Ingalls. Chalk and a lawman he believed he could trust rode to the Yantes cabin and they hid along the path a few feet away from the entrance. Chalk concluded that Yantes would have to travel the path the following morning in order to take care of his horses.

When Yantes appeared, Chalk ordered him to throw up his hands, but instead of doing what the officer ordered, the bandit attempted to run. The plan had been for the deputy to shoot the desperado if he offered resistance while Chalk watched in case other members of the gang were there. The mist had dampened the caps of the deputy’s gun and when he failed to fire Chalk believed the lawman had been betrayed. Chalk fired on Yantes just as the woman ran from the house with the bandit’s revolver. Yantes was fatally wounded and died before Chalk could get him to Ingalls.

Chalk collected the reward offered by the state, the banks, the railroads, and the insurance company for the apprehension of any member of the Doolin Gang, dead or alive.

In addition to serving three terms as sheriff of Ford County, Chalk also served as a representative of the area in the state legislature from 1902 to 1906. Chalk’s abilities extended beyond his work in law enforcement and politics. He was an accomplished horse trainer and an expert musician. He could play the violin, trombone, and French horn. In 1885 Chalk founded the Dodge City Cowboy Band. The band was made up of more than eighteen men who played brass, percussion, and strings. The Dodge City Cowboy Band performed at the Long Branch Saloon, owned by Chalk, and entertained local citizenry by marching in parades. The band wore their best cowboy attire, including their six guns, which they fired in the air to punctuate a chord or musical phrase.

The tough and talented Chalk met his demise on August 8, 1912. Three days prior to his death, Chalk was sitting atop his horse at the C.O.D. Ranch, watching a nearby road construction crew work. His mount was suddenly spooked. The horse bucked and reared and before Chalk was able to get the animal under control it threw him hard against the saddle horn. Chalk never recovered from the serious injury.

Chalk Beeson’s well-attended funeral was held on August 11, 1912, at his ranch. Local businessmen and luminaries spoke highly of the contributions he had made to the community. Benevolent and fraternal society members, as well as civic and church representatives, turned out to brag about all he had done to make Dodge City a safe place to live. Mourner s reflected on Chalk’s fine character and of the positions of responsibility and trust he held in Ford County. One of Chalk’s friends at the funeral admitted that the community believed that “just one of Chalk Beeson’s strengths could withstand the worst kind of injury.”

To learn more about Chalk Beeson and other legendary western figures when you read More Tales Behind the Tombstones.

This Day…

| 1912 | Colonel Theodore Roosevelt announces that he will run for president if asked. |

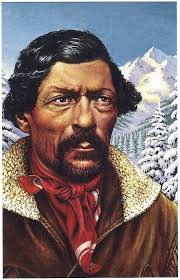

Tales Behind James Beckwourth’s Tombstone

Enter now to win a copy of More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

James Beckwourth was one of the most legendary mountain men of the early 1800s. He was the son of a Maryland Irishman and a slave girl, and he was born in Virginia in 1798. When he was very young, his family moved to St. Charles, Missouri. James worked as an apprentice to a blacksmith until the age of nineteen, when he left the anvil and the forge to sign on as a trapper with the Missouri Fur Company, then challenging Hudson Bay trappers working the rich beaver streams beyond the crest of the Rockies.

In 1824, Beckwourth joined William H. Ashley and Andrew Henry on a fur-trapping expedition in the Rocky Mountains; he was one of the first trappers to go into the new country. During various expeditions, he participated in skirmishes with the Blackfeet and other Indians. He became skilled in the use of the bowie knife, tomahawk, and gun.

In 1828, he was adopted into the Crow Indian tribe. He packed his traps and buckskin shirts on his horses and moved to the headwaters of the Powder Rivers and into a new life among the ancient people. He proved himself quickly among his adopted people and rose to the position of war chief. His skill as part of a raiding party to steal Comanche horses was masterful. His prowess and bravery in battle against the hated Blackfoot Indians earned him the name Bloody Arm.

James Beckwourth helped make the Crow a more powerful nation. No more would they give away a tanned buffalo hide for a pint of trade whiskey. Bloody Arm knew the value of hides and the wiles of the whites. He knew the worth of powder and ball and traps and horses and finery for Crow women.

When a fur company opened a trading post among the feared Blackfeet, Beckwourth got the same company to make him its agent among the Crow to see that his adopted people were treated fairly in the trade of pelts for guns. When the beaver trade began fading, Beckwourth went to the Southwest and joined with another ex–mountain man to lead a war party of Utes to raid Spanish ranches in Southern California. They headed east with three thousand head of California horses.

He spent a while in Taos, moved onto Colorado to become a contract hunter supplying meat in places like Bent’s Fort, and then became a trader among Indians. Showing up again in Southern California, he raised a company of Yanquix to fight Governor Micheltorena of Mexico in a quickie revolution.

By the time of the California Gold Rush and the westward movement of hundreds of wagon trains over the worst passes of the Sierra, James, then in his fifties, led a wagon train over a sizable mountain pass that was to be named after him. He still had years of adventure before him. He scouted for the Third Colorado Cavalry tracking Black Kettle to Sand Creek and turned away in disgust at the massacre.

At the age of sixty-eight, Beckwourth embarked on another venture, this one in a bid for peace. The Oglala Sioux were pressing the Crow to join against the whites. The US Army sent for Beckwourth to advise his adopted tribe. He thwarted the alliance.

Mystery surrounds James Beckwourth’s death in Colorado in 1866 in a Crow village. Some historians note he was poisoned by a Crow warrior who caught him cavorting with his wife. The most reliable account of his passing reports that he was poisoned by order of the Crow’s tribal council because he would not accept their offer to go on the warpath with them again. If they could not keep him as a chief, they decided to have the honor of burying him in their burial ground near Laramie, Wyoming. Beckwourth was seventy-eight when he died.

Read More Tales Behind the Tombstones.

This Day…

More Tales Behind the Tombstones

Enter now to win a copy of

More Tales Behind the Tombstones:

More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious, Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

Visitors walking through the graveyards often find themselves stepping over weeds that have grown around fallen headstones. Sadly, the final resting place for many small families and communities has been left unattended or even forgotten. The seasons have taken with them the names chiseled in the granite, nearly erasing all memory of those mourned beneath the dilapidated tombstones.

Aside from the normal life and death cycle in New England, it is estimated that one in every seventeen people died on the journey west from 1847 to 1900. Oftentimes the men, women, and children who died en route to the gold hills of California and Colorado, or the fertile farmlands of the Pacific Northwest, were buried on the spot where they died. A proper burial and lengthy funeral were forfeited in favor of pushing on to the far-off destination. Traveling across the plains demanded that sojourners be constantly on the move. The threat of bad weather, hostile Indians, wild animals, or desperados kept pioneers from staying too long in one area.

Contrary to popular belief, the thousands of settlers who perished on the trail west did not solely die in gunfights or Indian attacks. Scorching deserts, starvation, and dehydration claimed many lives. Poor sanitation bred typhoid, cholera, and pneumonia. Blood poisoning brought on by a cut or scrape from a sharp object, or shock from an accident, such as a wagon spilling over with travelers inside, brought about numerous deaths as well.

There were pioneers, though, who could not be persuaded to forgo a ceremonial funeral if they lost a loved one. Nothing could keep them from burying the deceased in a plot where they could be remembered. A section of ground in a scenic location with trees to shade the grave was the preferred spot. To leave someone dear in an unmarked plot was impossible for some to accept.

As pioneers established homesteads and built towns around their farms and ranches, the dead were buried either in family cemeteries near where they had lived or next to churches where they worshipped. For nineteenth-century ancestors, it was important to remember death. The fact of death served as a reminder to those who continued on to persevere and do good works as preparation for a final judgment by a righteous God.

Whatever the cause of death or wherever it occurred, the need to take care of a deceased person’s remains was a necessity. Until the discovery of formaldehyde in 1867, and the subsequent introduction of the product and its use as an acceptable embalming method in America in 1872, there were limited ways to deal with the dead. Immediate burial was preferred. If a person died in the winter and the ground was frozen and a grave could not be dug, the body was stored in a barn or woodshed until the earth thawed and the departed could be buried.

As in the cities, carpenters in mining camps or cattle towns were usually the undertakers, since they had the tools and supplies to build coffins. The wooden caskets might be lined with white linen if it was supplied by the deceased’s family or friends. Sextons, people who looked after a church and churchyard, would determine where in the cemetery a person was to be buried. They would also dig the grave and fill it again.

People who lived in small towns would often gather at the graveyard where the coffin was placed atop two sawhorses. For those who lived in less rural areas, there were hearses to rent to transport the dead from the undertaker’s office to the cemetery. The vehicle had glass sides and was decorated with elaborate carvings and brass ornaments. On top were tall, shako-like plumes, one on each corner.

While cemeteries house the dead, the tombstones record not only their pleasures, sorrows, and hopes for an afterlife, but also more than they realize of their history, ethnicity, and culture. In this book are true stories about thirty real people who are buried in marked and unmarked graves throughout the frontier and elsewhere. How these famous and infamous individuals lived and then exited this world is reflected on their headstones. Tales of their demise add details of their courage, adventure, hardship, and joy not included on those tombstones.

The dead included in the book More Tales Behind the Tombstones will never exhaust their potential to enlighten.

This Day…

Whiskey & Wild Women

In Dodge City, Kansas, the important men made their headquarters at the Long Branch Saloon, opening in 1883 by Charles Bassett, Ford County’s first Sheriff, and A. J. Peacock. The Long Branch offered a high-toned sporting atmosphere, with only top-grade liquor served at the bar. Its customers included railroad men, cattle kings, buffalo hunters, and travelers. The saloon took its name from the celebrated sporting resort on the Atlantic seaboard, since many of the men in Dodge came from the Eastern states. There was no “Miss Kitty” and no dancing in the original Long Branch. In 1876, there were nineteen placed licensed to sell liquor in Dodge. Other well-known saloons on Front Street were Beatty and Kelley’s Alhambra; A. B. Webster’s Alamo; Muellar and Straeter’s Old House Saloon; the Opera House Saloon; the Junction Saloon; and the Green Front. Of course, all the dance halls and most of the hotels had bars, and no one in Dodge was more than one hundred yards from some place of liquid refreshment, open seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day. When a new saloon was opened or a new management took over, a magnificent free lunch was laid out and the men were expected to come to the joint to celebrate.

As railroad service improved and Dodge became more prosperous, carload after carload of beer rolled in every summer. In July 1879, a facetious note appeared in the Dodge City Times:

“A young lady, Miss Ann Heiser, is stopping the city at present. A great many gentlemen have called upon her and express themselves well pleased with her general appearance. The early criticism we have heard made is that the length of her neck is a little out of proportion to that of her body. The ‘out of proportion’ is to enable the fellows to embrace the neck. Ann Heiser is a delusion too many persons hug. It brings them to their beer.”