Enter now to win a copy of

More Tales Behind The Tombstones:

More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws,

Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

Sheriff Bill Tilghman

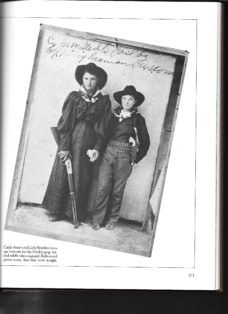

“A deputy marshal and a posse arrested two notorious female outlaws. … One was in men’s clothing.”

—August 21, 1895 edition of Evening Gazette, Cedar Rapids, Iowa

On the afternoon of August 18, 1895, United States Marshal Bill Tilghman and Deputy Marshal Steve Burke led their horses toward a small farm outside Pawnee, Oklahoma. The lawmen had tracked a pair of outlaws to the location and were proceeding cautiously when several gunshots were fired.

Marshall Tilghman caught sight of a Winchester rifle sticking out a broken window of a dilapidated cabin. He spurred his horse out of the line of fire just as the weapon went off. He steered his mount around the building and arrived at the backdoor the same time sixteen-year-old Jennie Stevens, alias Little Britches, burst out the house. She shot at him with a pistol while racing to a horse waiting nearby.

By the time Marshal Tilghman settled his ride and drew his weapon Jennie was on her horse. She turned the horse away from the cabin, kicked it hard in the ribs, and the animal took off. Tilghman leveled his firearm at the woman and shot. Jennie’s horse stumbled and fell, and she was tossed from the animal’s back, losing her gun in the process.

The marshal hopped off his own ride and hurried over to the stunned and annoyed runaway. Jennie picked herself up quickly and cursed her misfortune. She charged the lawman, dug her fingernails into his neck, and slapped him several times before he could subdue her. He was a battered man when he finally pinned her arms behind her back.

Back at the cabin, Deputy Marshal Steve Burke wrestled a gun away from thirteen-year-old Annie McDoulet, alias Cattle Annie, a rail-thin young woman wearing a gingham dress and a black, wide-brimmed straw hat. The pistol she had tried to shoot him with was lying in the dirt several feet in front of her.

Two years prior to their apprehension and arrest, Cattle Annie and Little Britches were riding with the Doolin gang, a notorious band of outlaws who robbed trains and banks. Enamored by the fame of the well-known criminals, the teenage girls had decided to leave home and follow the bandits. They helped the criminals steal cattle, horses, guns, and ammunition and warned them whenever law enforcement was on their trail.

Legend tells that Bill Doolin, leader of the Doolin gang, gave Cattle Annie and Little Britches their nicknames. Cattle Annie was born Anna Emmaline McDoulet in Kansas in 1882. Jennie Stevenson was born in 1879 in Oklahoma. Both girls had run afoul of the law before joining the Doolin gang. Each sold whisky to Osage Indians. According to the September 3, 1895, edition of the Ada, Oklahoma, newspaper the Evening Times, Jennie seemed to have “plied her vocation for a long time successfully, going in the guise of a boy tramp hunting work.” In between selling liquor to Indians and life with the Doolins, Jennie had married a deaf mute named MidKiff and Annie rustled livestock.

News of Cattle Annie and Little Britches’ arrest was reported in the August 21, 1895 edition of the Cedar Rapids, Iowa newspaper the Evening Gazette. “A deputy marshal and a posse arrested two notorious female outlaws but had to fight to make the arrest,” the article read. “The marshal’s posse ran into them and they showed fight. Several shots were fired before they gave up. One was in men’s clothing.”

The teenage outlaws were held in the jail in Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory until a trial was held. They were found guilty of horse stealing and sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment at the Farmington Reform School in Massachusetts. Cattle Annie and Little Britches were model prisoners and only served three years of their sentence.

Annie returned to Oklahoma Territory, where she met and married Earl Frost in March 1901. The couple divorced after eight years. In 1912 Annie married a house painter and general contractor named Whitmore R. Roach. They had two sons and lived a respectable life in Oklahoma City. Annie McDoulet Frost Roach died from natural causes on November 7, 1978, at the age of ninety-five. Her obituary ran in the November 8, 1978, edition of the Oklahoma City newspaper The Oklahoman. The article noted that “she was a retired bookkeeper and member of the American Legion Auxiliary and the Olivet Baptist Church. She had five grandchildren and thirteen great-grandchildren. She was laid to rest at Rose Hill Burial Park in Oklahoma City.”

To learn about More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen read

More Tales Behind the Tombstones