Enter now to win a copy of

Cowboys, Creatures and Classics: The Story of Republic Pictures

On December 7, 1941, radios buzzed with news that several hundred Japanese planes attacked a US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, killing more than twenty-four hundred Americans as well as damaging or destroying eight Navy battleships and more than one hundred planes. Though it would be some time before people learned the full scope of the damage, within days a once distant war in Europe and the Pacific became a central part of life in the United States, affecting politics, business, media, and entertainment.

Hollywood went to war along with the rest of the country. Prominent actors enlisted in the armed forces; actresses joined the Red Cross and volunteered their services to the USO. Notable motion pictures executives took part in the effort, too. Darryl Zanuck from 20th Century Fox got into the Army Signal Corp., and Jack Warner of Warner Brothers was assigned to the Army Air Corp. Studio heads unable to join the military fought the battle from behind their desks producing films about the scene overseas and the gallant men and women protecting our freedom. By the summer of 1942, more than 125 pictures had been completed, or were in the process of being shot, that reflected war and its various angles or dealt with men in the fighting forces. Those pictures depicted the sterner side of the national and international war scene in not only dramas, features, and short subjects but also in comedies, cartoons, and even musicals.

Hollywood was instrumental in shaping the resolve of the American public during the gloomy days of World War II. President Franklin Roosevelt used American’s love affair with the movies to keep the public firmly behind the war effort. He was instrumental in creating the Office of War Information. The Office of War Information created campaigns to enhance public understanding of the war at home and abroad; to coordinate government information activities; and to act as a liaison with the press, radio, and motion picture industry. The Office of War Information was heavily involved in regulating Hollywood studios as they churned out war films at breakneck speed. Films like Warner Brother’s Confession of a Nazi Spy and 20th Century Fox’s The Purple Heart helped galvanize the American public against two brutal enemies.

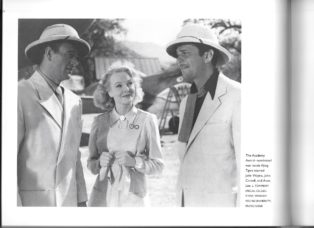

Republic Pictures also contributed to the awakening of the country’s citizenship as to whom the fight was against and why. Republic’s Flying Tigers, also known as Yank Over Singapore, was released on October 8, 1942. The movie was a tribute to the American Volunteer Group of pilots who battled the Japanese against overwhelming odds long before Pearl Harbor. According to the November 15, 1942, edition of the Hutchinson News, “Thrills abound in the picture which is a continuous series of stirring air duels between the outnumbered Americans and the Japanese.”

John Wayne has the principal role as leader of the American Volunteer Group. Anna Lee is a nurse in a hospital nearby. Paul Kelly, John Carroll, and Edmund MacDonald are pilots. The Hutchinson News noted that “some of the fight and injury scenes are strong medicine.”

To learn more about the many films Republic Pictures produced read

Cowboys, Creatures and Classics: The Story of Republic Pictures