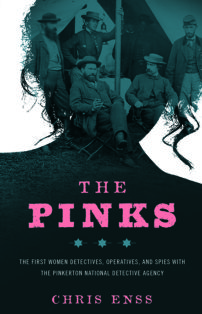

Enter for a chance to win a copy of

The Pinks: The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the

Pinkerton National Detective Agency.

1878- Round Rock , Texas- Sam Bass, Frank Jackson, AKA Blockey , and Seaborn Burns, arrived at Round Rock with the intention of robbing the town bank the next day. Lawmen were waiting for them, having been tipped off by Jim Murphy, a remaining gang member. In a store next to the bank, the gang killed Deputy Ellis Grimes and wounded Morris Moore. As they left the store, outlaw Seaborn Barnes was shot to death . Bass and Jackson shot their way out of town. Sam Bass was hit in the back. Later that day a company of Texas Rangers found him under a tree dying. He died without revealing Jackson’s destination, and the final member of the Bass gang was never found. If, in the end Bass revealed the location of the loot he acquired over a lifetime of crime, Jackson may have retired as a prosperous man.

Jack Zahran, president of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, wrote the foreword for The Pinks. I’m honored he contributed to the book.

When Allan Pinkerton founded the Pinkerton Detective Agency in 1850, he not only became the world’s first “private eye,” he also established an organization that would set the global standard for investigative and security excellence for generations to come.

But the agency had only just begun the process of setting that standard when Kate Warne walked into Allan Pinkerton’s office six years later and asked for a job. Her request was well timed. Pinkerton was keenly focused on new opportunities and was consciously looking to make bold choices that reinforced his vision of Pinkerton as an innovator and a disruptor.

Warne’s confidence and persuasive skills were impressive, and Pinkerton’s flexibility and willingness to “defy convention” perhaps equally so. It is to his credit, and to the enduring credit of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, that it took Pinkerton less than twenty-four hours to inform Warne that he would hire her—a decision that made her the nation’s first female detective. It was a remarkable turn of events at a time when only 15 percent of women held jobs outside of the home, and contemporary ideas about what constituted “women’s work” severely limited employment opportunities for women.

Kate Warne, and the accomplished women who played such an important role in building the Pinkerton Detective Agency into an iconic global security and law enforcement institution, made it abundantly clear that the prevailing definition of “women’s work” was not just inadequate, but wholly obsolete.

Kate’s story, and the stories of all of these remarkable female operatives—presented so beautifully and in such rich detail here in this fascinating and important book—are not just a moving reminder of the achievements of a handful of bold pioneers, they are also a remarkable testament to the exemplary tradition of innovation that has distinguished the Pinkerton name over the course of more than a century and a half of dedicated service.

Allan Pinkerton was very clear about the fact that he wanted his company to be fearless and to have a “reputation for using innovative methods to achieve its goals.” What is remarkable is not just the aspiration, but the execution: This founding vision would grow into a long-standing tradition of innovation and a commitment to inspired service that became intricately woven into Pinkerton’s organizational DNA.

Pinkerton’s enduring legacy of bold moves, brave choices, and the relentless pursuit of excellence is much more than just an aging résumé—it is the foundation for an organization that remains on the cutting edge. Today, the company that predates the Civil War not only remains relevant, but has continued to establish itself as a dynamic and innovative presence on the world stage. Pinkerton is a recognized industry leader in developing forward-looking security and risk management solutions for national and international corporations. Remarkably, an organization that once protected Midwestern railways and pursued famous outlaws like Jesse James and Butch Cassidy is now providing sophisticated corporate risk management strategies and high-level security services for clients across the globe, setting a twenty-first-century standard for corporate risk management.

Now, as then, Pinkerton understands that combating new and emerging threats and serving its clients requires a willingness to challenge conventional wisdom, and embrace new assets and new ideas—whether they are the world’s first female detectives or new cybersecurity protocols. From investigative and private detective work to security and corporate risk consulting, Pinkerton prides itself on doing whatever it takes to keep its clients safe and to protect their assets and their interests. That resolve is one of the biggest reasons why an agency that was protecting Abraham Lincoln was also on the ground in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, and why the principles and practices that were in place almost eighty years before the discovery of penicillin still apply to an organization that provides risk management services to some of the world’s most innovative enterprises in 2016.

As you read and enjoy these fascinating profiles of gifted Pinkerton operatives, you will readily see how their work and their character exemplified the agency’s values of Integrity, Vigilance, and Excellence. Ultimately, those attributes are at the heart of these tales, and at the heart of the larger Pinkerton story. It’s a history that spans three centuries, with compelling new chapters still being written each and every day.

1897- the Klondike gold rush began with the arrival of the treasure ships Portland and the Excelsior at Seattle, Washington bearing miners from the Yukon, who carried suitcases and boxes full of gold. Thousands began to book passages north after the miners spread tales of fortunes waiting to be made. The gold had been discovered in August 1896 on a tributary of the Klondike River later named Bonanza Creek. News of a strike in Nome, Alaska, ended the stampede in 1898. It’s estimated that by then prospectors had spent $50 million reaching the Klondike, about the same amount taken from the diggings in the five years after the first strike.

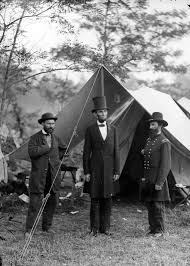

President-elect Abraham Lincoln showed no sign of being nervous or apprehensive about the late night ride Pinkerton operatives arranged for him to take on February 23, 1861. Kate Warne noted in her records of the events surrounding Mr. Lincoln leaving Pennsylvania that he was cooperative and congenial.

When the politician arrived at the depot in Baltimore with his colleagues and confidants, Ward Hill Lamon and Allan Pinkerton, he was focused and quiet. He was stooped over and leaning on Pinkerton’s arm. The posture helped disguise his height, and when Kate greeted with a slight hug and called him “brother,” no one outside the small group thought anything of the exchange. For all anyone knew, Kate and Mr. Lincoln were siblings embarking on a trip together. Neither the porter nor the train’s brakeman noticed Mr. Lincoln as the president-elect. Kate made it clear to the limited, railroad staff on board that her brother was not well and in need of solitude.

It took a mere two minutes from the time the distinguished orator reached the depot until he and his companions were comfortably on board the special train. The conductor was instructed to leave the station only after he was handed a package Pinkerton had told him to expect. The conductor was informed the package contained important government documents that needed to be kept secret and delivered to Washington with “great haste.” In truth the documents were a bundle of newspapers wrapped and sealed.

The bell on the engine clanged, and the train lurched forward. The gas lamps in the sleeping berths in Mr. Lincoln’s car were not lit, and the shades were pulled. Kate and Pinkerton agreed it would be best to prevent curious passengers waiting at various stops from seeing in and possibly recognizing the president-elect. No one spoke as the train slowly pulled away from the station. All hoped the journey would be uneventful and were hesitant to make a sound for fear any conversation might jeopardize what had been done to get Mr. Lincoln to this point. It was Mr. Lincoln who broke the silence with an amusing story he had shared with Pennsylvania governor Andrew Curtain the previous evening.

“I used to know an old farmer out in Illinois,” Mr. Lincoln told the three around him. “He took it into his head to venture into raising hogs. So he sent out to Europe and imported the finest breed of hogs that he could buy. The prize hog was put in a pen and the farmer’s two mischievous boys, James and John, were told to be sure not to let it out. But James let the brute out the very next day. The hog went straight for the boys and drove John up a tree. Then it went for the seat of James’ trousers and the only way the boy could save himself was by holding onto the porker’s tail. The hog would not give up his hunt or the boy his hold. After they had made a good many circles around the tree, the boy’s courage began to give out, and he shouted to his brother: ‘I say, John, come down quick and help me let go of this hog.’

Mr. Lincoln’s traveling companions smiled politely and stifled a chuckle. Had the circumstances been different, perhaps they would have laughed aloud. Undaunted by the trio’s subdued response, the president-elect continued to regale them with amusing tales of the people he’d met and experiences they shared. The train gained speed and soon Philadelphia was disappearing behind them.

Perhaps it’s because I like my agony in widescreen that I so appreciate any Sergio Leone movie. Or perhaps it’s the reoccurring theme of the bad guy getting his due that’s so appealing. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Leone was the most esteemed film director of the sixties. The popularity of his debut Western, A Fistful of Dollars (1964), turned Clint Eastwood into a worldwide star and founded the ‘spaghetti western’ style. U.S. publicists called Eastwood’s hero ‘The Man With No Name’, which became his name. Fistful’s success ensured two sequels: For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). These films became very popular, resulting in dozens of imitative European westerns. As Leone noted, ‘They call me the father of the Italian western. If so, how many sons-of-_____ have I spawned?’ Conservative estimates exceed 500.

Once Upon a Time in the West is not only my favorite Leone film, but my favorite film period. Key Largo runs a close second. Claire Trevor’s performance in Key Largo is spectacular. Once Upon a Time in the West is the quintessential ‘bad guy gets his due’ flick. Charles Bronson plays the protagonist and proves as Pete Townsend once said, “All the best cowboys have Chinese eyes.” Henry Fonda, with his shocking blue eyes, is the villain. Bronson pursues Fonda through the entire film. Fonda has committed a crime against Bronson and his brother and he can’t live a full life until he makes sure Fonda pays for what he’s done. The shootout between Bronson and Fonda is like every other shootout in a Leone film. It’s grand and the pacing makes you feel every anxious moment. The bad guy goes down. When he looks into the face of the person he’s wronged he knows exactly what he’s done. He’s not necessarily sorry for his actions, but he is fully and completely aware of what he’s done. That’s what makes Once Upon A Time in the West great. For me it fulfills the overwhelming desire to see justice served here and now. Fonda’s character doesn’t die to serve as a model for what will happen to all bad guys if they don’t do right. Fonda’s character dies because of what he did to Bronson’s character’s brother. It doesn’t matter if anyone else knows why he was killed. It only matters that the bad guy knows. Real life bad guys get away with murder. They go on with their lives without a care in the world, without a moments thought to the lives they’ve ruined by their actions. It must be wonderful to look into the face of the bad guy as she goes down for her crime and know that she is completely aware of what got her to the ‘point of dying.’ Think I’ll watch Once Upon a Time one more time.

Today’s focus isn’t on The Pinks, but that doesn’t mean you can’t still

Today’s focus isn’t on The Pinks, but that doesn’t mean you can’t still1861-Rock Creek, Nebraska-Gunman David McCanles, enraged at Hickok’s seeing his mistress, went to the Rock Creek station, standing outside the cabin and calling for Hickok to come outside. Hickok refused and McCanles went to a side door. It is unclear whether or not he pulled his six-gun. “Come out and fight fair!” McCanles shouted. Hickok did not step outside. Then McCanles shouted that he would go inside the cabin and drag Hickok outside. “There’ll be one less s.o.b. if you try that,” Hickok shouted back. McCanles then entered the side door of the cabin and Hickok shot him through the heart. McCanles’ 12-year-old son, Monroe, ran into the cabin to hold his dying father.

Reviewed by Meg Nola

June 27, 2017

The Pinks reads like a historical thriller, with the fascinating plot twist of being based wholly on truth.

Chris Enss’s The Pinks offers an engrossing look at the women’s flank of the famed Pinkerton group, which provided services of security, protection, investigation, and, in many cases, infiltration by its initially all-male staff of “private eyes.”

Pinkerton had an innovative and invasive approach to dealing with crime and criminals. After immigrating to the United States from Scotland, he eventually established the Pinkerton offices in Chicago. Six years after the agency opened, Kate Warne had the audacious foresight to apply for a job as a Pinkerton detective, despite the fact that Pinkerton himself had never considered hiring women. Warne argued that women could assume undercover roles as ably as men, and that feminine intuition and charm could help them excel as undercover agents.

Though Pinkerton knew the work would be dangerous, he hired Warne and assigned her to numerous cases. Enss depicts Warne as an excellent actress, able to alter her appearance, accent, and mood quickly and convincingly. Pinkerton’s investigations were often complex and went on for extended periods of time as the agents gained the confidence of key individuals—or the guilty parties themselves. Warne rose to every challenge, including escorting a disguised Abraham Lincoln to Washington via train in 1861. The then president-elect was in danger of assassination by a Baltimore cadre of secessionists who wanted Lincoln dead before he even had a chance to take office.

The Pinks notes how Warne’s success encouraged Pinkerton to employ other women, placing them in roles of general investigation or even espionage during the Civil War. They pursued murderers, carried classified documents, decoded messages, and maintained their cover in highly charged situations. Ultimately, the Pinkerton logo became that of a watchful female eye, accompanied by the apt motto of “We Never Sleep.” However, despite Allan Pinkerton’s equal-opportunity mind-set, official American police forces did not hire female detectives until the late nineteenth century.

The Pinks details Kate Warne’s career as a Pinkerton detective, along with various other cases assigned to female agents like Hattie Lawton, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, and the artistically gifted Lavinia “Vinnie” Ream. Filled with intrigue, suspense, bravery, and women’s accomplishment, The Pinks reads like a historical thriller, with the fascinating plot twist of being based wholly on truth.

1890- Wyoming became the 44th state. Wyoming was named after an Algonquin Indian word meaning ‘large prairie place’. Appropriately, the Indian paintbrush that covers much of the large prairie is the state flower and the meadowlark, frequently seen circling the prairie land, is the state bird. Another Indian term, Cheyenne, is also the name of the state capital. Wyoming is called the Equality State because it is the first state to have granted women the right to vote (1869).