| 1891 | The American Association moves its Chicago franchise to Cincinnati to compete with the National League’s after withdrawing from the National Agreement, thus starting a war with the rival league. The circuit will fold in end of the year, resulting in the Baltimore Orioles, St. Louis Browns, Louisville Colonels, and Washington Senators becoming National League teams the next season. |

Path to Righteousness

Take a chance. Enter to Win a copy of the

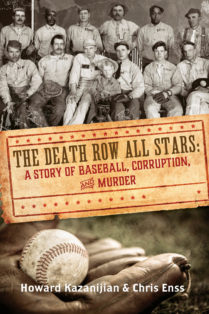

Death Row All Stars: The Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.

ostensibly to make sure his property was being maintained properly. He also would be able to monitor other activities at the prison, such as Warden Alston conferring with murderer George Saban on the baseball field. Gramm would have a firsthand look at the players who enjoyed fame of a sort— their names at one time or another resting on the tongues of men who had seen them operate; their faces known, having been posted in newspapers and on sheriffs’ boards along with the list of crimes they had committed.

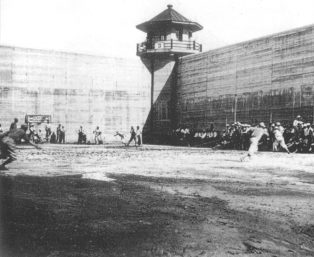

On July 18, 1911, under a blue and cloudless sky, the murderers, burglars, rapists, and confidence men that made up the Death Row All Stars emerged quickly from the baselines of the baseball diamond at the penitentiary and spread across the practice field for their first game. Alston, Gramm, and a host of other prison officials, as well as inmates, were on hand to watch. Inmates craned their necks to see the action from their barred windows and cheered the players on as they whipped the ball from base to base. Warden Alston had supplied the team with gloves, bats, and uniforms, and the ball club look

It was evident after practicing with the other men on the team only a short while that Joseph Seng was an exceptional baseball player. News of the talented addition to Alston’s All Stars spread quickly throughout the area. Patrons who frequented the Turf Exchange, the Senate, the Elkhorn, and other watering holes in Rawlins, speculated on how well the team would do against more established ball clubs in the region. George Saban encouraged such talk whenever he made stops at the saloons as part of his duties transporting items to and from the prison accompanied by prison guard D. O. Johnson in the penitentiary wagon. Security was always lax where Saban was concerned. He came and went from tavern to tavern as he pleased and boasted about the baseball team he helped manage.

Betting on baseball was commonplace in 1911, regardless of its legality. Partnering with a drifter named George Streplis, a man who had been arrested in March 1911 in Wyoming and held over for trial on gambling charges, Saban had plans to capitalize on the trend of betting on baseball games by urging patrons at saloons in Rawlins to bet heavily on the Death Row All Stars. Any ideas Saban had about placing bets on the penitentiary ball club were tabled, however, until he knew how long Seng would be at the Rawlins facility. He didn’t want to gamble on the team if Seng wasn’t going to be at the prison long enough to play with the All Stars. An appeal of his sentence had been filed with the governor immediately; on June 15, 1911, Governor Carey responded favorably to the appeal, and, on July 18, 1911, the Chief Justice Board of the state Supreme Court granted a stay of execution in his case.

Regardless of the fact that his time as head of the prison lessee program was coming to an end, Otto Gramm believed he had some lingering influence at the facility. He did own all the equipment and material used to manufacture the brooms, and, as long as that was the case, he would insist on being a part of the business, visiting the penitentiary and played like professionals. There was no infighting, and players didn’t discuss the specifics of their criminal history with one another. The focus was the game.

The stories of the men who took to the field were varied. Shortstop Joseph Guzzardo had killed a woman in 1908 while shooting at a man who was threatening his life. Eugene Rowan, the first baseman, had been convicted of breaking and entering and attempted rape in Cheyenne. Right fielder and catcher James Powell had attacked a young woman. Team captain George Saban had pled guilty to three killings. And catcher and fielder Joseph Seng had been sentenced to death for the murder of a man in Uinta County.

Every time a player came to bat and slapped a ripping fastball on the nose for a solid hit to left field or someone snatched up a red-hot grounder and heaved it to the proper base to get an out, the All Stars forgot they were little more than caged creatures. Warden Alston and Saban stood on the baselines conferring on strategies of the game, discussing when a good bunt would beat a strong hit and how best to utilize each player. But the ever-watchful Gramm believed that their conversation went deeper than that. Prison guard D. O. Johnson had reported to Gramm that Saban was illegally betting on the All Stars’ games using money given to him by Warden Alston. Gramm relayed the information to Senator Francis Warren, who suspected the rumor might have a future and that Governor Carey, who had handpicked Warden Alston for the job, was also involved. Senator Warren once said of Governor Carey, “If I hadn’t known Carey from the time he stepped off the train in 1869, a green boy up to the present, and hadn’t figured inside of the inner circles so much with him in political affairs, he might possibly fool me once in a while, for he surely is the most monumental hypocrite, and the most infernal liar—when necessary—that God ever permitted to live.

To learn more about the inmates who played ball at the Crossbar Hotel read the

Death Row All Stars: The Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.

This Day…

Life at the Crossbar Hotel

Enter to Win a copy of the

Death Row All Stars: The Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.

The sheriff of Uinta County delivered Joseph Seng to the state penitentiary on April 18, 1911. An endless blue sky was the backdrop for the massive, three-story structure that day. High, barbed wire fence lined the building on all sides, and a plaque on the structure read “Welcome to the Crossbar Hotel”. Felix Alston, who had taken over the duties of prison warden the day before, watched Seng arrive. A pair of guards helped the shackled and handcuffed prisoner out of the vehicle in which he was transferred. The iron-barred door in front was opened, and Seng was escorted inside the penitentiary. The doors were then closed and locked behind him.

According to Joseph Seng’s family, his father, Anthony, had cried when he read an article about his son in the April 22, 1911, edition of the Wyoming Press. “On last Monday morning Sheriff Ward and Special Deputy Sam Rider took Joseph Seng, the convicted murderer of William Lloyd, to the penitentiary where the man will be confined until he is executed,” the report announced. “Seng was handcuffed to Sheriff Ward . . . he passed through the streets of Evanston thus manacled; he was smoking a cigar, and was accompanied by his customary indifference as to the gravity of the situation.”

There was a standard routine for admitting an inmate into a state facility. The guards would lead a prisoner into an intake room and remove his shackles and chains. They would remove all items from the prisoner’s pockets and set them aside on a table to be inventoried. The prisoner was then ordered to remove his clothes. A guard carrying a fire hose would enter the intake room and point the hose at the prisoner. When the water was flipped on, the force generally slammed the prisoner back against the stone wall. After a few moments, the water was shut off, and the guards would pull the prisoner to his feet. A huge scoop of delousing powder was then tossed on him. Gasping and coughing, blinking powder from his eyes, the prisoner was then shoved toward a trustee cage, a small, defined area where the “trustee,” an inmate who had proven himself trustworthy and had been given a job within the prison, was separated from the prisoner by a thick wall of wire rope with a small slot in it.

To learn more about the inmates who played ball at the Crossbar Hotel read the

Death Row All Stars: The Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.

This Day…

Outlaws in the Infield

Time to Enter to Win a copy of the

Death Row All Stars: The Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.

Few spectators would have bet against Joseph Seng when he was catching for All Stars pitcher Thomas Cameron. Cameron, a twenty-year-old coal miner and native of Tennessee, had a terrific fastball and was a good hitter. Seng, the standout performer on the team, signaled the talented pitcher on what throw to use. Under Seng’s direction Cameron struck out the majority of batters that faced him.

Born in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in 1882, Seng came from a large German family. His father, Anthony Seng, was a proud man who had been born in Baden, Germany. He moved to the United States with his parents in 1878 and married Anna Sapple in the Sacred Heart Church in 1880. All of Anthony and Anna’s children were christened at the parish. Just before the turn of the century, Joseph Seng had been a laborer at one of the textile mills in the area. From 1903 to 1908 he resided in New York, and some history records indicate he worked for a prominent railroad line as a detective. Then, after a brief visit with his parents in Allentown in the summer of 1908, the twenty-six-year-old Seng departed for points west.

Baseball had always been part of Seng’ life. According to notes made by his spiritual advisor, Reverend Peter Masson of the Church of the Sacred Heart in Allentown, Joseph had a “natural aptitude for baseball, but never displayed ambition for much else.” Still, he didn’t appear to be much of a troublemaker. In fact, the brown-haired, blue-eyed Seng was a diminutive five-foot-five and was said to have a very moderate temper. “He never shied away from long hours on the job,” Reverend Masson continued, “and was mindful to give an employer all that was required of him and then some.”

After Seng stepped off the train in Rawlins, Wyoming, in July 1908, he walked to one of the saloons just beyond the railroad tracks. Reverend Masson’s notes about the letters he received from Seng painted a picture of his visit to the saloon:

When he entered the business he heard the sound of chips clinking from a side room. A bartender was behind the bar pouring drinks. Patrons were scattered about talking and laughing. Joseph found a spot at a table and sat down. He ordered something to drink while studying the “help wanted” section of a newspaper left behind on the chair next to him.

Customers filtered in and out of the establishment, some exchanged a word or two with a couple of men near the bar. Before walking away from the men the patrons handed them money. Like many saloons throughout the West, gamblers had staked out their territory and were enticing people to wager on boxing and wrestling matches, horse races and political races.

A reading of the Rawlins Republican between May and June 1908 might have led to the conclusion that there was wide interest in stamping out vice in the region—or at least regulating it for the better of the community. In fact, gambling had been outlawed statewide in 1902, but in many communities, it was still widely accepted and officials followed a strict policy of pretending not to notice the poker games and bookmakers in local saloons.

To learn more about the inmates who played for their lives read the

Death Row All Stars: The Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.

This Day…

The Captain and the Critic

Enter to win a copy of the book

Death Row All Stars: A Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.

Sheep rancher Joe Emge woke up fast from a fitful slumber late on a chilly night in early April 1909 near Spring Creek, Wyoming. There was no light inside the wagon where he and one of his ranch hands had bedded down. When the darkness around him began to break up and his eyes slowly adjusted, he saw the dim, blurred outline of a man standing over him. Joe squinted and strained to focus on the object the imposing figure was pointing at him. When he realized the object was a six-shooter, it was too late.

Cattleman George Saban pulled the trigger back on his .35 automatic and fired a shot into Joe’s face. He quickly pulled the trigger back again and slapped the hammer with his left hand; it was the fastest way to get off several more shots. The objective was to not only kill Joe but also the other man in the wagon. It was a job the gunman dispatched with ease and no regret.

George jumped out the vehicle and stood in a pool of firelight cast by a smoldering campfire. He heard gunfire erupting inside a second wagon close by, and he turned to see what had happened.

Joe Allemand, a sheep rancher with a bullet hole in his back, stumbled out the wagon, picked himself up, and staggered away from the scene, his hands in the air. Two gunmen, Herb Brink and Ed Eaton, stepped out of the wagon behind him. Herb leveled his Winchester at Joe and fired. Joe lurched forward and fell hard in the dirt, dead. “It’s a hell of a time at night to come out with your hands up,” Herb quipped.

Herb marched over to a stand of sagebrush, gathered a handful, and placed the end into the campfire. The brush crackled and snapped as it burned. He held it up in the air and watched the flame grow then tossed it under the wagon nearest him. In a matter of moments the vehicle was engulfed in fire. George followed Herb’s lead, grabbed a fistful of dry vegetation and dipped it into the flames licking the wheels of the wagon.

As the three men watched the fire burn and consume the vehicles and the gear around it, the report of a series of gunshots in the near distance was heard. Four of George and Herb’s cohorts had unloaded their weapons into a large herd of sheep. The few animals that managed to escape scattered, bleating loudly as they ran away.

George walked over to his horse which was tied to an old, rain-bleached post and lifted himself into the saddle as though he hadn’t a care in the world. He nudged his ride away from the chaos and trotted off into the shadows of the landscape, leaving the others to follow after him.

To learn more about the All Stars and the games they played to save their lives read

The Death Row All Stars: A Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.

This Day…

A Fast Game

Enter to win a copy of the book

Death Row All Stars: A Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.

A blinding, hot sun pushed its way out from behind a few clouds and stretched across a baseball diamond above Overland Park in Rawlins, Wyoming, in the summer of 1911.1 A crowd of people in the stands of the shade-free arena carved into the center of town waved cardboard fans in front of their faces in a futile attempt to push the merciless heat away from them. All eyes were trained on Thomas Cameron, a cherub-faced, overly tired baseball player on the pitcher’s mound. He backhanded beads of sweat off his forehead as he stepped away from his position and looked over the fielders behind him.

Some of his teammates slapped their fists into their rough, well-worn gloves, and all shouted words of encouragement. Thomas adjusted his cap and pulled it down far over his forehead. He kicked the dirt under his feet, and a haze of powdery dry dust rose in the air around his ankles and settled on his grimy uniform. He stepped back onto the mound and readied himself to pitch. His arms rose high over his head as he started his wind up. Rearing back on his left leg he fired a wild, high fastball. The alert batter turned away from the plate while fading backwards to avoid the out of control pitch, but the ball ricocheted off his left shoulder and bounded back into the stands.

A fat, unkempt umpire shouted for the batter to take his base. The spectators hissed at the rattled Thomas. He cast a glance at the team captain, George Saban, near the dugout and noticed the grim expression on his face.* It was an unfortunate error. Thomas’s shoulders sagged under the weight of what he knew could happen because of the mistake.

To learn more about the All Stars and the games they played to save their lives read

The Death Row All Stars: A Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.