He would have been fifty-three tomorrow. He was murdered by people that work at Liberty Hospital and TallGrass Technologies.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

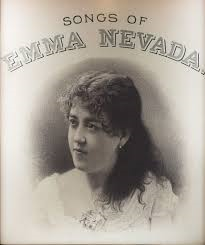

Doc Wixom lifted his three-year-old daughter and stood her carefully in the middle of a table. Wrapped in an American flag, golden brown ringlets framing her sweet face, Emma Wixom smiled at her audience. The church on the banks of Deer Creek was crowded with miners and merchants, teamsters and saloonkeepers. They were there to benefit a local charity, and the sight of a child symbolized the hopes of the future.

Unafraid of the eager faces crowed around the table, little Emma Wixom knew what was expected of her. She was happy to sing on this lovely morning. She did it all the time, unaccompanied, singing for the pure love of the sound.

That summer day in 1862, in the thriving California Gold Rush town named Nevada, she gave a performance to remember. Inside the Baptist church on the banks of Deer Creek, Emma took a deep breath and released a pure soprano voice that held the audience spellbound. By the time the last note sounded, there was not a dry eye in the house. Brawny, wet-cheeked miners showered her with nuggets of pure gold.

Emma Wixom, the daughter of a country doctor, began a long and illustrious career that day in the church. She would go on to sing opera in Europe and America. She would draw standing-room-only crowds to her performances, but her biggest fans remained the reckless, rugged gold miners who first took a little child into their hearts.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

Dutch Carver, a half-drunk gold miner, burst into Eleanora Dumont’s gambling house and demanded to see the famous proprietor. “I’m here for a fling at the cards tonight with your lady boss, Madame Mustache,” Carver told one of the scantily-attired women draped across his arm. He handed the young lady a silver dollar and smiled confidently. “Now you take this and buy yourself a drink. Come around after I clean out the Madame and maybe we’ll do a little celebrating.” The woman laughed in Dutch’s face. “I won’t hold my breath,” she said.

Eleanora Dumont soon appeared at the gambling table. She was dressed in a stylish garibaldi blouse and skirt. Her features were coarse and there was a growth of dark hair on her upper lip. At one time she had been considered a beautiful woman, but years of hard frontier living had robbed her of her good looks. It had not, however, taken away her ability to play poker. She was the first and best lady card sharp in California. Her skills had only enhanced with age.

Eleanora sat down at the table across from Dutch and began shuffling the deck of cards. “What’s your preference?” she asked him. Dutch laid a wad of money out on the table in front of him. “I don’t care,” he said. “I’ve got more than two hundred dollars. Let’s get going now, and I don’t want to quit until you’ve got all my money, or until I’ve got a considerable amount of yours.”

Eleanora told him that she preferred the game vingt-et-un (twenty-one or blackjack). The cards were dealth and the game began. In a short hour and a half Dutch Carver had lost his entire bankroll to Eleanora.

When the game ended the gambler stood up and started to leave the saloon. Eleanora ordered him to sit down and have a drink on the house. He took a place at the bar and the bartender served him a glass of milk. This was the customary course of action at the Twenty-One Club. All losers had to partake. Eleanora believed that “any man silly enough to lose his last cent to a woman deserved a milk diet.”

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

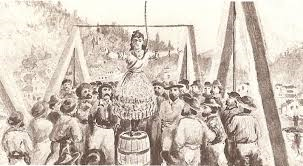

Juanita slowly walked to the gallows, took the noose in her hands, and adjusted it around her neck. She pulled her long, black hair out from beneath the rope so it could flow freely. A blanket of silence fell over the crowd watching the hanging in Downieville, California, that sunny July afternoon in 1851.

Less than twenty-four hours before, the people in this California Gold Rush town had been celebrating the country’s independence. The streets were still lined with bunting and flags. A platform still stood in the center of the town where prominent speakers had given patriotic lectures. There had been bands and parades. Drunken miners had brawled in the streets and bartenders had rolled giant whiskey barrels into tent saloons for everyone to have a drink. It had been a momentous occasion – the first Fourth of July celebration since California had become a state.

Juanita was one of a couple of thousand people who had taken up residence in this pine-covered mountainside burgh, three thousand feet across the upper Yuba River. Downieville was the richest region in the Gold Country. Ninety-two thousand dollars worth of gold had been found in the area in the first half of 1850.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

Rain dripped steadily from the bare trees outside the dark parlor. The bride stood at the top of the stairs, a red rose sent from her best friend pinned inside her dress. Unveiled, she started down the steps to the man who waited to marry her.

She had resisted his courtship and insisted that marriage did not fit her plans. The young engineer standing at the foot of the staircase had made his own plans. He arrived out of the wild West with a “now or never” declaration. He had taken off his large, hooded overcoat, placed his pipe and pistol on the bureau in the room that had belonged to the bride’s grandmother, and the quiet force of his intent carried the day.

The bride well knew that the Quaker marriage ceremony puts the responsibility for making the vows directly on those who must keep them. She descended the stairs, catching sight of her parents, a handful of other family members, her best friend’s husband, and the man she had finally agreed to marry.

Mary Hallock gripped the arm of Arthur De Wint Foote and stepped up in front of the assembly of Friends, as the Quakers called themselves, to speak those irrevocable vow. She was twenty-nine, with an established career as an illustrator for the best magazines of the day. She had carefully considered what she would give up by taking this step. Arthur was a mining engineer, and his work was in the West. She was an artist, and all her contacts were in Boston and New York. She faced forward with a mixture of anxiety and joy.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, California, in 1848 set off a siren call that many Americans couldn’t resist. Enthusiastic pioneers headed west intent on picking up a fortune in the nearest stream. Though only a few actually used a pickax in the search for a fortune, women played a major role in the California Gold Rush. They discovered wealth working as cooks, writers, photographers, performers, or lobbyists. Some even realized dreams greater than gold in the western land of opportunity and others experienced unspeakable tragedy.

Nancy Kelsey stood on the porch of her rustic home in Jackson County, Missouri, watching her husband load their belongings onto a covered wagon. Soon, the young couple and their one-year-old daughter would be on the way to California. She hated leaving her family behind and she knew the trip west would be difficult, but she believed she could “better endure the hardships of the journey than the anxieties for an absent husband.”

Nancy was born in Barren County, Kentucky, in 1823. She married Benjamin L. Kelsey when she was fifteen. She had fallen in love with his restless, adventurous spirit, and from the day the two exchanged vows she could not imagine her life without him. At the age of seventeen, Nancy agreed to follow Benjamin to a strange new land rumored to be a place where a “poor man could prosper.”

Nancy, Benjamin, and their daughter, Ann, arrived in Spalding Grove, Kansas just in time to join the first organized group of American settlers traveling to California by land. The train was organized and led by John Bidwell, a New York schoolteacher, and John Bartleson, a land speculator and wagon master.

Nancy’s recollections of some of the other members of the Bidwell-Bartleson party and the apprehension she felt about the trip were recorded in the San Francisco Examiner in 1893. She described what it was like when the wagon train first set out on its way on May 12, 1841: “A man by the name of Fitzpatrick was our pilot, and we had a priest with us who was bound for the northwest coast to teach the Flathead Indians. We numbered thirty-three all told and I was the only woman. I had a baby to take care of, too.”