Enter now to win a copy of Tales Behind the Tombstones and More Tales Behind the Tombstones:

More Deaths and Burials of the

Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen

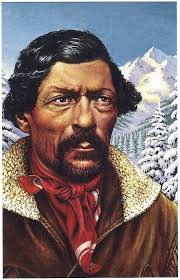

James Beckwourth was one of the most legendary mountain men of the early 1800s. He was the son of a Maryland Irishman and a slave girl, and he was born in Virginia in 1798. When he was very young, his family moved to St. Charles, Missouri. James worked as an apprentice to a blacksmith until the age of nineteen, when he left the anvil and the forge to sign on as a trapper with the Missouri Fur Company, then challenging Hudson Bay trappers working the rich beaver streams beyond the crest of the Rockies.

In 1824, Beckwourth joined William H. Ashley and Andrew Henry on a fur-trapping expedition in the Rocky Mountains; he was one of the first trappers to go into the new country. During various expeditions, he participated in skirmishes with the Blackfeet and other Indians. He became skilled in the use of the bowie knife, tomahawk, and gun.

In 1828, he was adopted into the Crow Indian tribe. He packed his traps and buckskin shirts on his horses and moved to the headwaters of the Powder Rivers and into a new life among the ancient people. He proved himself quickly among his adopted people and rose to the position of war chief. His skill as part of a raiding party to steal Comanche horses was exceptional. His prowess and bravery in battle against the hated Blackfoot Indians earned him the name Bloody Arm.

James Beckwourth helped make the Crow a more powerful nation. No more would they give away a tanned buffalo hide for a pint of trade whiskey. Bloody Arm knew the value of hides and the wiles of the whites. He knew the worth of powder and ball and traps and horses and finery for Crow women.

When a fur company opened a trading post among the feared Blackfeet, Beckwourth got the same company to make him its agent among the Crow to see that his adopted people were treated fairly in the trade of pelts for guns. When the beaver trade began fading, Beckwourth went to the Southwest and joined with another ex–mountain man to lead a war party of Utes to raid Spanish ranches in Southern California. They headed east with three thousand head of California horses.

He spent a while in Taos, moved onto Colorado to become a contract hunter supplying meat in places like Bent’s Fort, and then became a trader among Indians. Showing up again in Southern California, he raised a company of Yanquix to fight Governor Micheltorena of Mexico in a quickie revolution.

By the time of the California Gold Rush and the westward movement of hundreds of wagon trains over the worst passes of the Sierra, James, then in his fifties, led a wagon train over a sizable mountain pass that was to be named after him. He still had years of adventure before him. He scouted for the Third Colorado Cavalry tracking Black Kettle to Sand Creek and turned away in disgust at the massacre.

At the age of sixty-eight, Beckwourth embarked on another venture, this one in a bid for peace. The Oglala Sioux were pressing the Crow to join against the whites. The US Army sent for Beckwourth to advise his adopted tribe. He thwarted the alliance.

Mystery surrounds James Beckwourth’s death in Colorado in 1866 in a Crow village. Some historians note he was poisoned by a Crow warrior who caught him cavorting with his wife. The most reliable account of his passing reports that he was poisoned by order of the Crow’s tribal council because he would not accept their offer to go on the warpath with them again. If they could not keep him as a chief, they decided to have the honor of burying him in their burial ground near Laramie, Wyoming. Beckwourth was seventy-eight when he died.