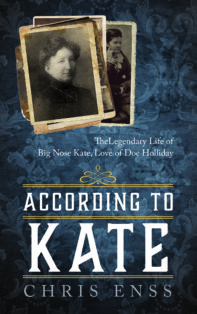

According to Kate is coming soon to bookstores everywhere.

In honor of her imminent arrival this month is dedicated to

Wild Women like Kate Elder.

With the end of the Mexican War in 1846 and the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in California two years later, the West was opened with a rush. Thousands upon thousands of Easterners – adventurous, avaricious, or discontented – left their homes to try their skill and luck in the wild West. It was long before the names of such boomtowns as San Francisco, Deadwood, Tombstone, Leadville, and Denver became bywords back East.

Soon after the birth of any new boomtown, it was ready to swing into its first phase of growth. Hustle was the name of the game. Hustle to get the choice town lots. Hustle to get the first shipment of new merchandise. Hustle to build the first saloon, the first gambling palace, the first brothel. There were great profits to be made, but the gamble was equally great. The old warning of “haste makes waste” was never in the thoughts of the boomtown entrepreneurs. Their only object was to dig the gold and silver from the miners’ pockets before someone else did, to get a piece of the trail hands’ hard-earned cash before it was all spent.

In the rush, all types of people appeared. The first was the prospective saloonkeeper, who knew he was starting a sure thing. Not long after him came the girl of the “line,” the row of small houses on the outskirts of town where prostitutes plied their time-honored trade. A successful and ambitious chippy might aspire to become a fancy madam, operating a first-class parlor house.

Typically, the first saloon in a nascent boomtown was a tent in which a board was set across two barrels to form a bar. The saloonkeeper ladled out his whiskey in tin cups to the thirsty men. By the time the proprietor shifted his established to a sturdier structure, he might have procured a few girls to sell their services to the patrons of the bar. The saloonkeeper’s next step was the acquisition of a piano, and pianist, both brought into the boomtown at great trouble and expense.

At the time of the Mexican War, the keyboard virtuosos were playing “Clarin de Campana” or “The Trumpet of Battle.” Then when the California gold rush came along, the favorite was “Hang town Gals.” Through the 1880’s and 1890’s, saloon music was quieter and more romantic: “Little Annie Roonie,” “You’re the Flower of My Heart, Sweet Adeline,” “She’s More to be Pitied Than Censured,” “A Bird in a Gilded Cage.” At the turn of the century, after Scott Joplin wrote his “Maple Leaf Rag,” the popular songs the “Professor” played all had a ragtime jingle – except when both pianist and patrons were weepily drunk. At such times, usually in the wee hours of the morning, the man at the ivories would play, with many eloquent and fanciful hand gestures, the sentimental and slower-paced songs of Stephen Foster, or perhaps “Genevieve,” “After the Ball,” or “Only One Girl in the World for Me.”

When a preacher invaded the dim precincts of demon whiskey to bring “The Work” before it was too late, he was treated with courtesy, even when his host was assailed as “a fiend in human form.” The poker players threw in their cards and pocketed their chips and the bar was closed as the evangelist mounted the Keno platform. The proprietor and the bartenders stood with folded arms during the devotions, then joined heartily in song as the piano played “Jesus, Lover of My Soul.”

There was no architectural standard for the early Western saloon. The tent served for a year or so, until it could be replaced by a structure of log or clapboard, or adobe. In short, the saloon was fashioned from whatever was most readily available. Seldom did the exterior have visual appeal, and never did it need it. Visual appeal was to be found inside, at the foundation of the entire business – the bar

From about 1840 to 1880, bar-making was one of the country’s significant crafts, with many a wood smith reaching the pinnacle of his art in designing the fixtures for a saloon. Crude chairs and tables were good enough for gambling, but the bar – had to show a richness which would suggest quality to the men who were bending an elbow. As a saloon prospered and acquired tone and class, the decorations grew more elaborate. Not uncommon were such grand features as red plush curtains, thick rugs instead of sawdust, and fancy chandeliers which sprayed a mist of perfume on the sweaty dancers below.

In almost every saloon the major attraction was a nude and nubile girl painted life-size on a canvas which hung just above the eye level of the men at the bar. Many a proprietor would bet that in any given twenty-four-hour period no patron would enter his place without casting a glance at the nude. And no one has heard of a bartender who lost that bet. In the bigger saloons, one might see as many as a dozen examples of Saturday-night art.

Some emporiums would sell beer for a nickel a mug and whiskey for a dime a shot; others would charge as much as two bits for a glass of rotgut. Signs on the Cyrus Noble Saloon in West Texas proudly advertised, “Fire Water and Poor Cigars. Whiskey guaranteed under the National Pure Food Law.”

Fancy establishments prided themselves on stocking expensive imported beers. In 1880, Lowenbrau wholesaled out of Chicago at $15.25 for a case of fifty bottles, so the retail price of a bottle must have been upwards of sixty cents – more than it costs today! But it is hard to generalize about the retail price of booze in the Old West. The price depended on the brand, the year, and what the traffic would bear.

Many establishments advertised a “free lunch” to attract customers and, once attracted, keep them thirsting for more refreshment. The food was salted very liberally. Buffet tables filled with sliced bread, hot sausages, beef, pork, crackers, pretzels, and cheese were open to all who invested in a glass of beer.

The saloon was the hub of the Western town. Bar, restaurant, gambling house, town hall, hotel, brothel, and sometimes courtroom or church, the saloon was the first building constructed and the last business to go broke. In the early days of the frontier town, there was no lodge, club, or pool hall where the men might gather. So, when our rugged Western individualists felt the need for communal activity, they surged through the only doors available – the bat-wing doors of the saloon.

Since the leaders of the town hung around at the saloon, people went there to find them. If a miner was shot, his wife rushed to the saloon to get the Doc or the sheriff, or the mortician. If there was a nasty accident on the ranch, the injured man’s friends stuffed a dirty cloth in the wound, threw him across a horse and galloped into town and the saloon.

Death often visited the saloon. Take the case of Ezra Williams, who got himself badly shot in California. He was toted inside the local bar and stretched out on a table, under the hanging lamps, while Dr. Thomas D. Hodges removed the bullet.

Ezra groaned in pain.

“He’s mighty bad off,” said a gambler, “and I’ll bet he dies before sun-up.”

Doc Hodges, whose pride was deeply touched, angrily snapped back, “Fifty dollars says he don’t!”

“You’re on,” the gambler leered. “Anybody else want to bet?”

Within a few moments, over $14,000 was wagered on Ezra’s life or death. Dutch Kate, who later became a stagecoach robber, ambled in and bet a cool $10,000 Ezra would be on his feet before the sun shone again. For hours everybody crowded around to watch the man and the ticking clock. Finally, Ezra obliged Dutch Kate and checked out of the saloon only minutes before sun-up.

According to Kate: The Legendary Life of Big Nose Kate, Love of Doc Holliday

arrives in bookstores everywhere October 1.