1900 – President William McKinley signed the Lacey Act, 16 U.S.C. § 3371–3378, to defend fauna from poachers. It banned the illegal commercial transportation of wildlife. The conservation law was introduced by Iowa Rep. John F. Lacey. It has been amended several times. The most significant times were in 1969, 1981, and in 1989.

The Posse After Sam Bass

Enter to win a copy of

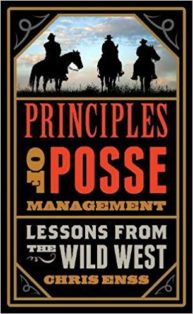

The Principles of Posse Management:

Lessons from the Old West for Today’s Leaders.

Nighttime overtook the Union Pacific train traveling west from Kansas City, Missouri, to Denver, Colorado, through Nebraska. The straight, single track stretched for miles over the desolate, shadeless, featureless land whose only trace of civilization was found in patches of plowed earth, rich and black, alternating with unfenced fields of young grain, and in a few lonely settlements of a half dozen houses. It was along this section of railroad in late September 1877 that the train relaxed its head long speed to a slower rate. It would run smoothly and steadily toward the water station of Big Springs, Nebraska. The passengers on board would get a respite from oscillating curves and erratic jolts and jars. The journey promised to be fairly uneventful with nothing to see apart from a lone tree in the sleepy town in the far distance.

Just before 10 o’clock, the Union Pacific train stopped in Big Springs. Station employees were not on hand to greet the vehicle as they usually did. Three armed gunmen, Jack Davis, Sam Bass, and Joel Collins, had tied up the station agent and his assistant and locked them in a closet. Before the engineer had a chance to leave the train to find the agent, Joel Collins jumped on board brandishing a weapon and demanded the engineer and the fireman throw up their hands. The cocked six-shooter aimed at their heads persuaded them to do as they were told.

With guns drawn, Sam Bass and Jack Davis boarded the express car and were ransacking its contents when they came upon a couple of safes. One of the safes was partially opened, and a large quantity of gold was inside. The thieves took possession of the gold and turned their attention to a second safe that was locked. Jack ordered the messenger to open the safe. He informed the gunman he didn’t have a key, but Jack didn’t believe him. He slugged the messenger over the head with the butt of the gun then thrust the revolver into the man’s mouth, knocking out one of his teeth in the process. Jack threatened to blow the top of his head off if he didn’t open the safe. All the man could do was shake his head. Sam convinced Jack the messenger was telling the truth and that they should move on.

To learn more about the great posses of the frontier read

The Principles of Posse Management:

Lessons from Old West for Today’s Leaders.

This Day…

1865 Flag flown at full mast over White House for the first time since Lincoln was shot.

In the Works

This Day…

Midwest Book Review

From the Midwest Book Review

The American History Shelf

Lone Star Books/TwoDot/Globe Pequot

www.globepequot.com

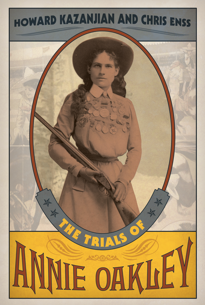

Two fine history books are recommended picks for history collections. Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss’ The Trials of Annie Oakley (9781493017461, $24.95) provides a biographical coverage that focuses on the feisty independent woman who advanced the image of women in American history both through her performances in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show and in her advocacy efforts. The latter – which included advocating for the US military and fighting for orphans – may be lesser-known episodes in her life, but here they are brought to the forefront in an account that reads with the lively immediacy of fiction but gathers a range of facts about Oakley’s performances and life. Bill Groneman’s Eyewitness to the Alamo (9781493028429, $18.95) gathers over a hundred descriptions of the Battle of the Alamo by those who were eyewitnesses, and traces the legends, realities and events of one of the most famous battles in American history. Discussions comment on reviews of the Alamo’s struggles and add the social and political background necessary to place these events in proper historical perspective. Both are recommended picks for any American history holding.

TwoDot/Globe Pequot

www.globepequot.com

Sherry Monahan with Jane Perkins’ The Golden Elixir of the West: Whiskey and the Shaping of America (9781493028498, $24.95) could have been featured in our Food and Wine section, but is reviewed here for its larger and central theme on the shaping of the West and how liquor – whiskey, in particular – played a big role in that history. From the evolution of the saloon business in the booming West to how California merchants became big whiskey shippers and how opulence developed in places whiskey was consumed, this provides a lively and thought-provoking story of the history of booze in the west. Sherry Monahan’s Tinsel, Tumbleweeds, and Star-Spangled Celebrations: Holidays on the Western Frontier from New Year’s to Christmas (9781493018024, $24.95) provides a lively history of holidays on the Western frontier and covers everything from traditions surrounding gifts and events to songs, poems, decorations and food and drink recipes. These come from firsthand stories of parties and events culled from journals, memorabilia, and newspaper reports, and covers the six major yearly holidays from New Year’s and Easter to Christmas and home-cooked to restaurant fare. Few books provide such an inviting approach as this; especially given the wealth of vintage illustrations throughout. Charlie Seemann’s Way Out West: Photographs from the Farm Security Administration 1936-1943 (9781493027279, $24.95) provides a lively history of the American ranch in the West, and is a ‘must’ for any Western Americana collection. While vintage black and white images are the backbone of this discussion, equally powerful and hard-hitting are surveys of dude ranches, individuals in the Farm Security Administration, bunkhouses and automobiles, and more. These are all top recommendations for any holding strong in Western Americana and American history.

This Day…

The Posse After Juan Soto

Enter to win a copy of

The Principles of Posse Management:

Lessons from the Old West for Today’s Leaders.

Sheriff Harry Morse removed a Model 1866 Winchester, carbine rifle from the leather holster on his saddle and cocked it to make sure he had a bullet in the chamber. He surveyed the sprawling canyon deep in the depth of the Panoche Mountain, more than fifty miles outside of Gilroy, California. In the distance below were three, small, adobe houses, and Morse had every reason to suspect members of outlaw Juan Soto’s gang were inside one of the buildings.

High above the sheriff and his eight member posse was a seemingly inexhaustible mat of black, rainless clouds moving steadily across the world. Morse watched the sun disappear behind the billows and exchanged a determined look with Captain Theodore Winchell on horseback next to him. Winchell, an undersheriff from Alameda County, had been riding with Sheriff Morse for several months in search of the fugitive. San Jose sheriff Nick Harris and six other deputies made up the rest of the posse. All the lawmen had years of experience tracking lawbreakers through the northern California terrain. Each was an exceptional shot and could hold his own in hand to hand combat.

Harry Morse had been sheriff of Alameda County for more than nine years. From 1864, when he took the job, to April 1871, when he peered down on the possible hiding place of Juan Soto’s men, Morse had traversed the hills and plains of eastern and northern Alameda County in search of horse thieves, highwaymen, and cutthroats. Until Morse took the job at twenty-eight years of age, most lawmen were afraid to venture too far to catch outlaws. Worried they would be outnumbered the criminals went about their business unconcerned they would ever be apprehended. Sheriff Morse, along with Nick Harris and Theodore Winchell, changed all that.

The officers and their deputies familiarized themselves with the haunts of the outlaws and the topography of the country where the bad guys were known to roam. They learned the locations of ranches, springs, and mountain trails as well as acquainted themselves with the inhabitants and their occupations. They knew where to hide and wait along trails for lawbreakers to pass, and, armed with that knowledge, they knew what to do to avoid an ambush.

Juan Soto, the man Sheriff Morse and his posse were tracking, was a thief and a murderer. He had a reputation as a brutal man who would stop at nothing to get what he wanted. Soto mainly operated in the central part of California but, like the other bandits before him, went wherever the possibility of loot beckoned him. For more than four years, the 6’2, two-hundred twenty pound, half-Indian, half-Mexican man had terrorized the area from the Livermore Valley to San Luis Obispo. Soto and his gang of desperadoes robbed stages, stage stops, lone emigrants, and prospectors. Their victims were often beaten or killed. Soto’s dark features and general express of animal ferocity earned him the name “the human wildcat.” He had black, slightly crossed eyes, a mane of black hair, and a bushy beard and mustache. The April 10, 1871, edition of the San Francisco Chronicle described his appearance as the “physical manifestation of as cruel a spirit as ever animated a human being.”

To learn more about the great posses of the frontier read

The Principles of Posse Management:

Lessons from Old West for Today’s Leaders.