1917 – Jeannette Rankin (R-MT) took her seat as the first female member of Congress

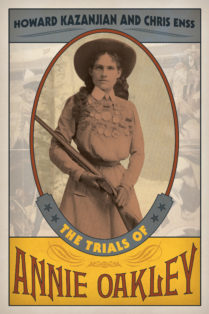

The Trials of Annie Oakley

Enter now to win a copy of

The Trials of Annie Oakley

Say the name Annie Oakley and the image of a young woman who could shoot targets out of the sky without a miss and rode across the frontier with Wild West showman Buffalo Bill Cody comes to mind. Annie Oakley was a champion rifle shot and did perform alongside well-known riders, ropers, and Indian chiefs in Colonel Cody’s vaudevillian tour, but there was more to Annie Oakley’s fame than her skill with a gun. The diminutive weapons wonder was a strong proponent of the right to bear arms, a noted philanthropist, and warrior against libel who fought the most powerful man in publishing and won.

The native Ohioan astonished the world with her almost unbelievable feats of rifle marksmanship. She could pepper a playing card sailing through the air, puncture dimes tossed into the sky, and break flying balls with her rifle held high above her head. She once shot steadily for nine hours, using three sixteen-gauge hammer shotguns which she loaded herself, breaking 4,772 out of 5,000 balls.

Annie Oakley fell in love with and married the first man she defeated in a rifle match one of the most noted marksmen in the West. Childless herself, she helped fund the care and education of eighteen orphan girls. The most deadly rifle shot alive, she was a beautiful, gentle woman, whose husband, Frank E. Butler died of a broken heart three weeks after her death in 1926.

Annie Oakley was a combination of dainty, feminine charm and lead bullets, adorned in fringed handmade fineries and topped with a halo of powder blue smoke. She had a reputation for being humble, true, and law abiding and was careful with her character at all times. When powerful, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst challenged her honor and questioned her respectability in his publication in 1903, Annie filed a lawsuit against him that’s still discussed at universities today.

To learn more about one of the most famous female sharp shooters

of the Old West read The Trials of Annie Oakley.

This Day…

Love and the Gold Miner

Enter now to win a copy of

Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women

Luzena Stanley Wilson stood in the center of her empty, one-room log home in Andrew County, Missouri, studying the opened trunk in front of her. All of her worldly possessions were tucked inside it: family Bibles, two quilts, one dress, a bonnet, a pair of shoes, and a few pieces of china. Mason Wilson, Luzena’s husband of five years, marched into the house just as she closed the lid on the trunk and fastened it tightly. They exchanged a smile, and Mason picked up the trunk and carried it outside. Luzena took a deep breath and followed after him. In a few short moments they were off on a journey west to California. It was May 1, 1849, Luzena’s birthday. She was thirty years old.1

The Wilsons were farmers with two sons: Thomas, born in September 1845, and Jay, born in June 1848. Three payments had been made on the plot of land the Wilsons purchased in January 1847. Prior to news of the Gold Rush captivating Mason’s imagination, the plan was to work the multi-acre homestead and pass the farm on to their children and their children’s children.2

Rumors that the mother lode awaited anyone who dared venture into California’s Sierra foothills prompted Mason to abandon the farm and travel to the rugged mountains beyond Sacramento. In addition to Luzena and her husband, their sons, her brothers, and their wives had committed to travel to California as well. A train of five wagons was organized to transport the sojourners west. On the off chance Mason never found a fortune in gold, the couple left behind funds with the justice of the peace to make another payment on their homestead. In the event the Wilsons were able to stake out a claim for themselves in the Gold Country, they would sell their Missouri home and use the proceeds to aid in their new life.3

“It was the work of but a few days to collect our forces for the march,” Luzena recorded in her journal shortly after they left on the first leg of their trip. “We never gave a thought to selling our section [of land], but left it. I little realized then the task I had undertaken. If I had, I think I should have stayed in Andrew County.” It would take five months for the Wilsons to reach their westward destination. Most of the belongings Luzena packed in their prairie schooner would be lost or left behind on the trail because they proved to be too burdensome to continue hauling.4

Luzena described the long journey west in her memiors as “plodding, unvarying monotony, vexations, exhaustions, throbs of hope and depth of despair.” Dusty, short-tempered, always tired, and with their patience as tattered as their clothing, the Wilson family and thousands like them plodded on and on. They were scorched by heat, enveloped in dust that reddened their eyes and parched their throats; they were bruised, scratched, and bitten by innumerable insects.5

Luzena’s Quaker upbringing in North Carolina had not prepared her for such a grueling endeavor. Her parents, Asa and Diane Hunt, had relocated from Piedmont, North Carolina, to Saint Louis in 1843, but the trip was comparatively easy. After the Hunts arrived in Missouri, they purchased a number of acres of land at a government auction. Luzena lived on the family farm until she and Mason wed on December 19, 1844.6

To learn more about Luzena Stanley Wilson and gold miner read

Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women

This Day…

| 1846 | William Frederick Cody, aka “Buffalo Bill” was born. |

Love and the Matriarch

Enter now to win a copy of

Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women

In September 1884, six weary journalists spent three unusually hot and humid days loitering around the New York harbor waiting for the world famous entertainer Lotta Crabtree to arrive. Lotta was on her way to the city where she had perfected her career. The moment her steamship docked, the scribes rifled through their pockets for pencils and notepads. They scribbled Lotta’s name across the tops of their notepads while anxiously waiting for her to appear. She had been away from the area for several years, performing on stages in New York, London, and Paris.1

Devoted fans, curious about what she would say when she stepped off the steamship America and looked around at the city that favored her, had gathered at the harbor. That her remarks would be voluminous, spirited, and to the point, no reporter or fan doubted. Journalists had been furnished with a little information about what she would say from her energetic manager, J. K. Tillotson. Tillotson had sent a short message to several newspaper editors across the country informing them that Lotta would make mention of her time abroad and address rumors that she had married in France. Reporters familiar with Lotta’s mother, Mary Ann Crabtree, thought it highly unlikely the red-headed star would have been allowed to do such a thing, but they had to be sure.2

Mary Ann was the quintessential stage mother. She was dedicated to seeing that Lotta became the best, most beloved actress on any stage. Toward that effort she had halted every romantic overture young men had made toward her daughter. Falling in love and getting married could interfere with the success Lotta worked so long and hard to achieve.3

Lotta was among the men and women making their way down the gangplank when the steamship finally docked and the passengers disembarked. According to various newspaper accounts, the thirty-seven-year-old star “looked very unassuming and was clothed like a little English servant girl out for a Sunday, in a loose blue dress without a suspicion of crinoline and a meek little Quaker bonnet. The only feature about the little lady which suggested her profession was her extraordinary red hair.”4

Lotta was greeted by a dozen or so lady fans that presented her with flowers and kissed her cheeks. The six weary reporters gathered around Lotta, and she looked up with surprise just as another woman was welcoming her with a kiss. “Miss Lotta,” a scribe said, ambling forward, the September 4, 1884, edition of the San Francisco Call reported. “I’m a representative of the press come to interview you. These are my colleagues. We want to write up something you will like.”

“I’ve nothing to say,” Lotta told them coldly. “Nothing whatsoever. Good afternoon.”5

“Miss Lotta,” said another,” “Mister Tillotson, your manager, wrote us letters about your arrival. Now, Miss Lotta, let us hear of your experiences. What of your recent nuptials?”

“Really,” said Lotta, in a tone that was just as cold as her last comment. “I can’t help what Mister Tillotson told you. I have nothing to say and no time to say it.”6

For five years newspapers had erroneously reported that Lotta had exchanged vows with three different men. In December 1879, the Daily Democrat in Sedalia, Missouri, claimed she met and married a man named W. H. Smith, a manager of a San Francisco theater. In July 1883, the Burlington Hawkeye in Burlington, New Jersey, reported that she married an O. Edwin Huss, and an article in the October 5, 1883, newspaper the Decatur Weekly Republican in Decatur, Illinois, read that she had wed Bolton Hulme.7

To learn more about Lottie Crabtree and the love she could have had read

Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women

This Day…

Love and the Pugilist

Enter now to win a copy of

Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women

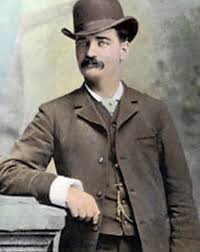

The Olympic Club Amphitheatre in New Orleans was filled to overflowing on January 14, 1891. Among the enthusiastic crowd that had converged on the scene was Bat Masterson, the charming, always well-dressed, part-time lawman, pugilist, and sportswriter. He sat closely to a twenty-four-square-foot boxing ring in the center of a massive room, under a bank of bright lights that surrounded the arena. Box holders and general ticket holders eager to see the fight between Jack Dempsey and Bob Fitzsimmons filtered through the main gate and quickly hurried to their assigned places. Security guards were stationed at several other entrances to the room keeping determined boxing fans from sneaking into the event without paying and barring entrance to any female who had a desire to see the highly publicized match.1

A competent announcer squeezed between the ropes carrying a speaking trumpet (predecessor of the megaphone) and positioned himself in the center of the canvas ring. In a clear, bold voice he introduced boxer Jack Dempsey to the more than four thousand spectators awaiting the action. Dempsey was escorted to the arena by his coach and his coach’s assistant. The twenty-eight-year-old boxer wore a determined expression. Fitzsimmons, also twenty-eight, looked just as resolute about the work to come when he appeared and was led to the ring. Cheers erupted for the pair. At the request of the referee both men shook hands and at the appropriate time began to fight.2

The audience and amphitheatre staff were transfixed on the action. Fans jumped to their feet at times and shouted instructions to the boxer they wanted to be victorious. A pair of guards at a side entrance of the club were so focused on the boxers in the ring they scarcely noticed the medium-height man pass by them wearing a derby hat, black coat, and tan trousers. The dark-haired, mustached gentleman kept an even pace with two men flanked on either side of him who appeared to be his friends. They exchanged a few pleasant words with one another as they made their way toward the ring. When the three reached the spot where Bat Masterson was seated, they stopped and the dapper man wearing the derby hat leaned down to speak to the Western legend. Bat looked away from the boxing match a bit surprised and smiled.3

A reporter sitting nearby witnessed the scene, jumped to his feet, and pointed at the person wearing the derby hat. “That’s a woman!” he shouted incredulously. Uniformed guards quickly swarmed the scene, grabbed the imposter’s arms, and swiftly ushered her toward the exit of the building. In the commotion the derby hat fell off and a curly mop of brunette hair tumbled out from under the hat. It was indeed a woman. It was Emma Walter Moulton, world renowned juggler and sometimes professional foot racer. She was there because her lover Bat Masterson was there, and she didn’t want to be away from him.4

To learn more about Bat Masterson and Emma Moulton read

Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women

This Day…

Love and the Outlaw

Enter now to win a copy of

Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women

A blazing hot sun shone through the branches of a few canadensis trees standing beside a crude wooden table in the patio of a small café in the town of San Vicente in Bolivia. The two men and one woman at the table pulled the chairs they were sitting on into the limited shade offered by the thin limbs of the trees. The city around them was noisy and crowded with people, some of whom were loud and nearly shouting their conversation to those with them as they made their way from one shop to another. Wagons without springs pulled by half-wild horses passed by, and the rattle of the wheels over the rocks and gravel added to the commotion.1

Robert LeRoy Parker, better known as Butch Cassidy, leaned forward in his chair in order for his friends to hear him over the racket in the street. Harry Longabaugh, also known as the Sundance Kid, and his paramour Etta Place leaned in closely to listen. Butch was regaling the pair with stories of the South American riches yet to be had by those willing to take them. Bolivia’s plateaus were filled with silver, gold, copper, and oil. Butch’s plan was to steal as much as they could of the income made by the people who mined or drilled for the resources there.2

Having spent much of their lives in the United States holding up trains and robbing banks, Butch and the Sundance Kid considered absconding with mining companies’ payroll shipments to be a natural course of events. Butch reasoned that law enforcement in Bolivia was lacking and their chances of getting away with the crime great. His point had been proven many times in the six years the outlaws had been in South America. Since arriving in Bolivia in 1902, the trio had robbed numerous banks and intercepted one mule train after another carrying gold and paper money.3

After migrating to the land-locked city, Butch, Sundance, and Etta discussed another heist. A mule train rumored to be transporting a rich payroll was going to be in the area. It traveled a little-known route outside of San Vicente. Butch had a plan to overtake the train and meet back at the café shortly after the job was done. His cohorts in crime thought the idea had promise and were enthusiastic about the opportunity.4

Twenty-eight-year-old Etta smiled happily at her two companions as the conversation strayed from the execution of the job to the large amount they had stolen. As the cheerful three laughed and reminisced about their crime wave, several members of the Bolivian Army surrounded the area. A gun suddenly fired, and a bullet almost took Butch’s head off. The two men quickly dove under the table. Sundance pulled Etta down with him. Bullets ricocheted around them as they surveyed the scene looking for a place to take cover.5

To learn more about Etta Place and the Sundance Kid read

Love Lessons from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women