1866- an Act of Congress authorized the creation of six regiments of Black troops, two of cavalry and four of infantry. These troops went on to play a major role in the history of the West, as the “Buffalo Soldiers.”

Operatives Elizabeth Baker & Mary Touvestre

Enter for a chance to win a copy of

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

Elizabeth Baker sat at a small, burl walnut desk, frantically scribbling on thick sheets of paper. A silhouette of her image cast on the fabric covered walls showed her flipping through the sheets paper. She was inspecting a variety of crude drawings of ships. The flame from a lit candle on the desk next to her danced in harmony with a draft seeping in through a closed window. It was early fall in 1861 in Richmond, Virginia. The Civil War was in its infancy, and military leaders from the North and South had sent spies behind enemy lines to learn whatever secrets they could.

Allan Pinkerton directed Mrs. Elizabeth H. Baker to go to the Confederate capital to acquire information about the Rebel navy. She didn’t hesitate to abide by the detective’s orders. Elizabeth had been working as an operative for the Pinkerton Detective Agency for a number of years. Although assigned to the Chicago office, she had traveled out of town on occasion, teaming with other agents to investigate robberies and missing person cases. Prior to moving to the Midwest, she had lived in Virginia and was well acquainted with the customs and the people of the region. When war broke out she relocated. Pinkerton referred to her as a “genteel woman agent” and considered her “a more than suitable” candidate for the assignment he’d selected for her.

Elizabeth wrote two sets of friends she had known from her days living in Richmond and informed them of her plans to visit. Claiming to miss being in Virginia, she told them she wanted to return and stay for a long visit. As luck would have it, Captain Atwater of the Confederate Navy and his wife invited Elizabeth to stay with them when she came to Richmond.

Elizabeth arrived at the Atwater’s home on September 24, 1861. The reunion was a happy one, and the three friends attended numerous receptions, balls, and fund-raisers together. Elizabeth met influential socialites, Confederate officers, and politically ambitious Southerners who claimed to possess the precise plans needed to defeat the North.

Drinks flowed at many of the soirees the Atwaters and Elizabeth were invited to attend. Tongues loosened at the events as the champagne and bourbon were consumed. One evening after having too much to drink, Elizabeth’s host decided to discuss the issues between the states and speculated on the tactics the Confederate navy would use to ensure the South would win the war. Elizabeth played her part well, agreeing with Captain Atwater about the North’s weaknesses and how much better life would be when the South defeated the Yankees.

When the three friends were not attending grand, social functions, they were touring the city. Elizabeth made mental note of the number of Confederate forces amassing in Richmond, the artillery being transported in and out of the city, and the fortifications being built around it. In the evenings before retiring to bed, Elizabeth jotted down everything she had seen and sketched the vital information on scraps of paper. She hid the notes and sketches in the crown of her bonnet.

To learn more about Elizabeth Baker & Mary Touvestre, the cases they worked, and the otherwomen Pinkerton agents read

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

This Day…

Operative Ellen

Enter to win a copy of

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

Several months before the start of the Civil War, Kate Warne was masquerading as a Southern sympathizer and keeping company with women of refinement and wealth from the South. When war did break out, those women were unafraid to express how much in favor they were of the Rebels. Some of them were secretly supplying the Confederate forces with information they had acquired using their feminine wiles. Kate was tasked with staying close to opponents of the government who were seeking to overthrow it and secure proof that secrets were being traded.

For weeks Kate had been monitoring the movements of Mrs. Rose Greenhow, a Southern woman believed to be engaged in corresponding with Rebel authorities and furnishing them with valuable intelligence. By late August 1861, Allan Pinkerton and a handful of his most trusted operatives, including Kate, had compiled enough evidence against Rose that a warrant for her arrest was granted. She was outraged when Pinkerton detective agents invaded her home and began gathering boxes of secret reports, letters, and official, classified documents. She called the agents “uncouth ruffians” and objected to her home being searched.

Pinkerton and his team left none of Rose’s possessions intact in their quest to extract all suspicious paperwork. The headboards and footboards of all the beds were taken apart, mirrors were separated from their backings, pictures removed from frames, and cabinets and linen closets were inspected. Coded letters were found in shoes and dress pockets. Among the items found in the kitchen stove were orders from the War Department giving the organizational plan to increase the size of the regular army, a diary containing notes about military operations, and numerous incriminating letters from Union officers willing to trade their allegiance to their country for a romantic interlude with Mrs. Greenhow.

According to Rose’s account of the inspection of her house and the seizure of many, sensitive letters, the “intrusion was insulting.” One of the investigators at the scene complimented her on the “scope and quality” of the material found. It was “the most extensive private correspondence that has ever fallen under my examination,” the operative confessed. “There is not a distinguished name in America that is not found here. There is nothing that can come under the charge of treason, but enough to make the government dread and hold Mrs. Greenhow as a most dangerous adversary.”

Pinkerton had hoped to keep the arrest quiet, but Rose’s eight-year-old daughter made that impossible. After witnessing the operatives foraging through her room and the room of her deceased sister, she raced out the back door of the house shouting, “Mama’s been arrested! Mama’s been arrested!” Agents chased after the little girl. Having climbed a tree nothing could be done until she decided to come down.

A female detective Rose referred to in her memoirs as “Ellen” searched the suspected spy for vital papers hidden in her dress folds, gloves, shoes, or hair. Nothing was found. Historians suspect the operative Rose referred to as Ellen was Kate Warne. Kate divided her time between guarding the prisoner and questioning leads that could help the detective agency track and apprehend all members of the Greenhow spy ring. Rose realized quickly that Kate was not someone to be trifled with, and she kept her distance.

In the days to come, several women suspected of being a part of Rose’s spy ring were also arrested and kept under lock and key with their leader at her house. The Rebel informer’s home was referred to as Fort Greenhow, and newspaper reporters flocked to the house of detention hoping to get a look inside and converse with the prisoners. The January 18, 1862, edition of Boston Post included an article about the home for inmates and described what it looked like. The article reported that Rose and her daughter had been confined to the upstairs portion of the residence and all other guests occupied the downstairs.

“We were admitted to the parlor of the house, formerly occupied by Mrs. Greenhow,” the article continued. “Passing through the door on the left and we stood in the apartment alluded to. There were others who had stood here before us we have no doubt of that, men and women of intelligence and refinement. There was a bright fire glowing on the hearth, and a tete-a-tete (an S shaped sofa on which two people sit face to face) was drawn up in front. The two parlors were divided by red curtains and in the backroom stood a handsome rosewood piano with pearl keys upon which the prisoners of the house, Mrs. G. and her friends had often performed.

“The walls of the room were decorated with portraits of friends and others, some on earth and some in heaven, one of them representing a former daughter of Mrs. Greenhow, Gertrude, a girl of seventeen or eighteen summers, with auburn hair and light blue eyes, who died sometime since.

“Just now, as we are examining pictures, there is a noise heard overhead, hardly a noise, for it is the voice of a child soft and musical. ‘That is Rosey Greenhow, the daughter of Mrs. Greenhow, playing with the guard,’ said the Lieutenant who noticed our inquisitive expression. ‘It is a strange sound here; you don’t often hear it, for it is generally quiet.’ And then the handsome face of the Lieutenant relaxed into a shade of sadness. There are many prisoners here, no doubt of that, and maybe the tones of this young child have dropped like rains of spring upon the leaves of the drooping flowers! A moment more and all is quiet, and save the stepping of the guard above there is nothing heard.”

To learn more about Kate Warne, the cases she worked, and the other

women Pinkerton agents read

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

This Day…

Operative Hattie Lewis

Enter to win a copy of

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

An article in the May 14, 1893, edition of the New York Times categorized women as the “weaker, gentler sex whose special duty was the creation of an orderly and harmonious sphere for husbands and children. Respectable women, true women, do not participate in debates on the public issues or attract attention to themselves.” Kate Warne and the female operatives that served with her defied convention, and progressive men like Allan Pinkerton gave them an opportunity to prove themselves to be capable of more than caring for a home and family.

Kate’s daring and Pinkerton’s ingenuity paved the way for women to be accepted in the field of law enforcement. Prior to Kate being hired as an agent, there had been few that had been given a chance to serve as female officers in any capacity.

In the early 1840s, six females were given charge of women inmates at a prison in New York. Their appointments led to a handful of other ladies being allowed to patrol dance halls, skating rinks, pool halls, movie theaters, and other places of amusement frequented by women and children. Although the patrol women performed their duties admirably, local government officials and police departments were reluctant to issue them uniforms or allow them to carry weapons. The general consensus among men was that women lacked the physical stamina to maintain such a job for an extended period of time. An article in an 1859 edition of The Citizen newspaper announced that “Women are the fairer sex, unable to reason rationally or withstand trauma. They depend upon the protection of men.”

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union played a key role in helping to change the stereotypical view of women at the time. The organization recognized the treatment female convicts suffered in prison and campaigned for women to be made in charge of female inmates. The WCTU’s efforts were successful. Prison matrons provided assistance and direction to female prisoners, thereby shielding them from possible abuse at the hands of male officers and inmates. Those matrons were the earliest predecessors of women law enforcement officers.

Aside from women hired specifically as police matrons, widows of slain police officers were sometimes given honorary positions within the department. Titles given to widows meant little at the time; they were, however, the first whispers of what would eventually lead to official positions for sworn police women.

Even with their limited duties, police matrons in the mid to late 1800s suffered a barrage of negative publicity. Most of the commentary scoffed at the women’s infiltration into the field. The press approached stories about police matrons and other women trying to force their way into the trade as “confused or cute” rather than a useful addition to the law enforcement community.

Allan Pinkerton’s decision to hire a female operative was all the more courageous given the public’s perception of women as law enforcement agents. Kate Warne had the foresight to know that she could be especially helpful in cases where male operatives needed to collect evidence from female suspects. She quickly proved to be a valuable asset, and Pinkerton hoped Hattie Lewis also known as Hattie Lawton would be as effective.* Hattie was hired in 1860 and was not only the second woman employed at the world famous detective agency, but some historians speculate was the first, mixed race woman as well.

To learn more about Kate Warne, the cases she worked, and the other

women Pinkerton agents read

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

This Day…

Operative Mrs. R. C. Potter

Enter to win a copy of

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

In the spring of 1858, a friendly, two-horse match race attracted the attention of many residents in the town of Atkinson, Mississippi. Mrs. Franklin Robbins and Mrs. R. C. Potter, both guests at one of the community’s finest hotels, had decided to see which one of their mounts was the fastest. They had begun their afternoon ride in the company of several others enjoying the balmy air, blooming flowers, and waving foliage of the sunny, southern landscape. Exploring a path that led to a bubbling stream, Mrs. Robbins and Mrs. Potter had lagged far behind the party and decided to narrow the gap when talk about who could make that happen first arose.

For a few moments, both the horses the women were riding ran at an uneven but steady pace; then suddenly Mrs. Robbins’ horse bolted ahead. Her ride didn’t stop until they reached the business district of town. Mrs. Robbins slowed the flyer to a trot before she glanced back to check on her competitor. Mrs. Potter was nowhere to be seen. Mrs. Robbins backtracked a bit; her eyes scanned the road she’d traveled. Her horse reared and threatened to continue the run, but she restrained the animal and pulled tightly on the reins. “Mrs. Potter!” she called out frantically, “Mrs. Potter?” Mrs. Robbins’ urgent cries drew the attention of the people with whom the pair had started the ride. They had congregated in front of the hotel when they heard Mrs. Robbins call for help. Not only did the fellow riders hurry to the scene, but men and women at various stores or saloons rushed to Mrs. Robbins’ aide.

Through broken tears she explained what had transpired and asked volunteers to accompany her in her search for Mrs. Potter. Many quickly agreed and wasted no time in following Mrs. Robbins. She spurred her horse back along the roadway they had just traveled.

The riders spread out in hopes of finding a trail leading to where Mrs. Potter’s mount might have carried her. One rider spotted a woman’s scarf caught in a low hanging branch of an oak tree and made his find public. Tracks near the tree led searchers to believe Mrs. Potter’s horse might have been spooked and out of control. After several tense moments trekking back and forth over field and stream, Mrs. Potter was located. She had been thrown from her ride and was lying motionless in a meadow adjacent to the home of the county clerk, Alexander Drysdale.

Mrs. Robbins rode to Alexander’s house and informed him of what had happened. In less than five minutes, he had improvised a stretcher out of a wicker settee and a mattress and had summoned four of his hired hands to help retrieve the injured Mrs. Potter. She was groaning in pain. She told those attending to her that her head hurt. In a few moments, the hired hands had lifted her off the ground and gently placed her in the settee. While being carried to Drysdale’s home, Mrs. Potter complained that her ribs were sore and her back was aching. Mr. Drysdale sent Mrs. Robbins and the other riders on their way and requested that Mrs. Robbins return with a physician. He promised that he and his wife would keep Mrs. Potter comfortable while waiting for the doctor to arrive.

To learn more about Kate Warne, the cases she worked, and the other

women Pinkerton agents read

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

Operative Kate Warne

Enter to win a copy of

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

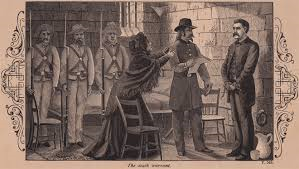

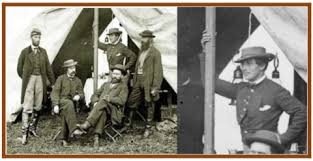

The person holding onto the tent pole has been mistaken as Kate Warne. No photo exists of Kate.

The depot of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad in Philadelphia was strangely bustling with an assortment of customers on the evening of February 22, 1861. Businessmen dressed in tailcoats, high-waisted trousers, and elaborate cravats milled about with laborers adorned in faded work pants, straw hats, and long dusters. Ladies wearing long, flouncy, bell-shaped dresses with small hats topped with ribbon streamers of blue, gold, and red mingled with women in plain brown skirts, white, leg-o- mutton sleeve blouses and shawls. Some of the women traveled in pairs conversing in low voices as they walked from one side of the track to the other. Most everyone carried carpet bags or leather valises with them.

The depot was the hub of activity; parent and child, railroad employees, and young men in military uniforms made their way with tickets in hand and destinations in mind. Among the travelers were those who were content to remain in one place either on a bench reading a paper or filling the wait time knitting. Some frequently checked their watches, and others drummed their fingers on the wooden armrests of their seats. There was an air of general anticipation. It was chilly and damp, and restless ticket holders studied the sky for rain. In the far distance, thunder could be heard rumbling.

At 10:50 in the evening, an engine and a few passenger cars pulled to a stop at the depot, and a conductor disembarked. The man was pristinely attired and neatly groomed. He removed a stopwatch from his pocket and cast a glance up and down the tracks before reading the time. The conductor made eye contact with a businessman standing near the ticket booth who nodded ever so slightly. The businessman adjusted the hat on his head and walked to the far end of the depot where a freight loader was pushing a cart full of luggage toward the train. The freight man eyed the businessman as he passed by, and the businessman turned and headed in the opposite direction. Something was about to happen, and the three individuals communicating in a minimal way were involved.

Three, well-built men in gray and black suits alighted from one of the cars as the freight man approached. One of the men exchanged pleasantries with the baggage handler as he lifted the suitcases onto the train, and the two other men took in the scene before them. Somewhere out of the shadows of their poorly lit platform, a somberly dressed, slender woman emerged. At first glance she appeared to be alone. She stood quietly waiting for the freight man to load the last piece of luggage. When he had completed the job and was returning to the ticket office, she walked briskly toward the train.

The woman’s hand and wrist were hooked in the arm of a tall man, dark and lanky, wrapped in a heavy, traveling shawl. He wore a broad-brimmed, felt hat low on his head and was careful to look down as he hurried along. When he and his escort reached the car, the woman presented her tickets to the conductor who arrived at the scene at the same time. “My invalid brother and I are attending a family party,” she volunteered. After examining the tickets for a moment, the conductor stepped aside to allow the pair to board. Protectively and tenderly, the woman took her brother’s arm and helped him to the stairs leading up the train. With an hint of reluctance, the lean, angular man climbed aboard.

To learn more about Kate Warne and the other

women Pinkerton agents read

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.